|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

There is a place on FIU’s smoke-free campus where cigarette smoking is allowed. But not just any cigarette. And only if you’re a robot.

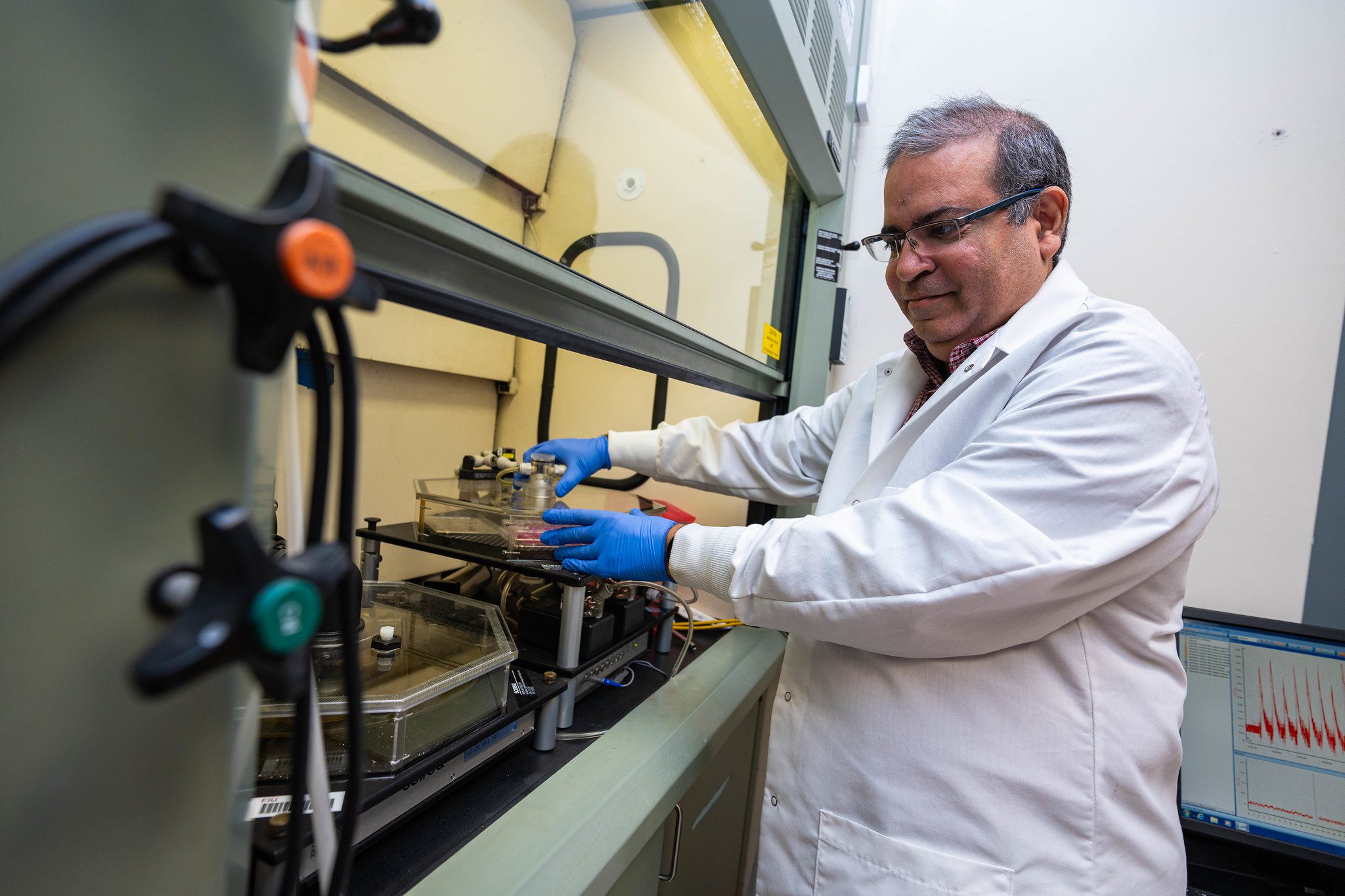

Professor Hoshang Unwalla, a researcher at the FIU Herbert Wertheim College of Medicine, uses research cigarettes specially made for laboratory tobacco research and a cigarette smoking robot to study the effects of smoking on HIV, the virus that causes AIDS.

“These are reference cigarettes with standardized components. They allow us to compare data across different laboratories involved in cigarette smoke exposure experiments,” says Unwalla. He emphasizes that researchers are not exposed to the smoke. The robot has an enclosed chamber where the cigarettes are lit. And the smoking machine is inside a fume hood with an external vent to prevent secondhand smoke exposure.

Since he joined FIU, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) has awarded Unwalla five grants, including three R01 grants totaling $5M for his research on smoking and HIV. And expected continuations could exceed $8M. The latest award is a $2.56 million grant from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute to study the airway epithelial transcriptome, the collection of RNA sequences in the layer of cells that cover the respiratory tract, in HIV-associated chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

Combination antiretroviral therapy, popularly known as drug cocktails, has made HIV infection a treatable chronic condition. However, Unwalla notes that HIV patients die almost a decade earlier than the HIV-negative population from comorbidities, including lung diseases like COPD, pulmonary hypertension and pneumonia, which are prevalent among people with HIV.

“These co-existing conditions are exacerbated in HIV patients who are addicted to nicotine and smoke tobacco,” says Unwalla. His laboratory focuses on identifying the factors that promote lung inflammation in people with HIV, hoping to develop drugs or other treatments that restore lung function or stop further deterioration.

In May, Unwalla and fellow College of Medicine researcher Srinivasan Chinnapaiyan received a patent for developing a CRISPR gene editing technique to suppress latent HIV reservoirs — groups of cells that are infected with HIV and can cause inflammation but are not producing infectious HIV. Antivirals do not work against these cells, and there’s always the threat they will start to produce virus.

“The ability of HIV to mutate its sequence and form latent reservoirs is a major impediment to developing a cure,” says Unwalla.

A way around it is to target the genes that help the virus replicate within cells. However, these human genes also have important cellular functions, and inactivating them can cause other harmful effects. Their newly patented CRISPR technique allowed Unwalla and his team to target in one embodiment a specific cellular gene critical for HIV—CyclinT1—only in HIV-infected cells.

“Using this approach, we demonstrated prolonged and robust silencing of HIV in HIV-infected cells.”

Unwalla believes silencing HIV in these cells “will decrease the incidence of comorbidities like COPD in people living with HIV.” And it will increase their life expectancy and quality of life.