|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

(Credit: U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum)

The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, DC, has just acquired a collection of never-before-seen photographs of an internment camp and imprisoned Jews in central France, which had been unknowingly stored in a Miami home for more than 30 years.

During a pandemic cleaning spree of her childhood bedroom, Miami resident Silvia Espinosa-Schrock came across a box that she had not thought about for three decades. As a precocious 19-year-old art student in New York City, Espinosa-Schrock had rescued a cardboard box of black-and-white photos she purchased on a sidewalk for $5 in January 1990. Espinosa-Schrock used the box of photos in an art installation assignment as a Cooper Union student, and later stored it in her childhood bedroom back in Miami.

“I had not seen these photos in about 30 years, having forgotten that I stored them in storage boxes in the closet,” said Espinosa-Schrock, an art history teacher at Miami Dade College.

When Espinosa-Schrock finally combed through and looked closely at the box’s contents, she found the name “Joachim Getter” written on one of the photographs. On a whim, Espinosa-Schrock conducted online research of the name and found one of Joachim Getter’s pictures posted on the “The Jewish Przemyśl Blog,” created by David Semmel, a descendant of the family.

In April 2020, Espinosa-Schrock reached out to Semmel, who resides in Bloomington, IN, and wrote: “I think I have something that belongs to your family.”

Many of Semmel’s family from Przemyśl (pronounced puh-SHEH-muh-shl), a town in Poland, were killed in the Holocaust.

“When I received the original photos from Silvia, I was overwhelmed to see pictures of my teenage mother, and also of my aunt Chaya and my uncle Joachim, whom we called ‘Muni’,” Semmel said. “After piecing together the family trees of the people in the photos using the JRI-Poland database, I realized how valuable this trove would be for Holocaust historians, and I contacted the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum. I didn’t want the collection to sit in my attic, and I hope someone someday might recognize the other people from the photos when they’re on the Museum’s collection website. Who knows? Another big discovery could happen.”

Suzy Snyder, a museum curator, assessed the collection and provided Semmel with documents to help him better understand the historical context of the collection.

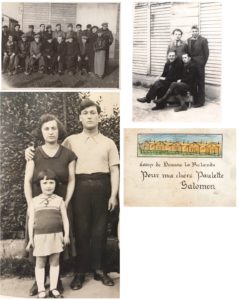

“The collection contains never-before-seen photographs of Beaune-la-Rolande, an internment camp in central France, 55 miles south of Paris, which the museum had limited visuals of,” Snyder said. “These images belong to Salomon Abend, as well as one drawing by him of the internment camp.”

According to the museum’s Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos, some 18,000 Jews were held in the Beaune-la-Rolande camp, with most of them deported to Auschwitz where they were killed. In March 1941, it became an internment center for Parisian Jews. The prisoners performed forced labor both inside and outside the camp.

“These photographs were sent from Salomon Abend to his then wife Paulette [born Perla Rosiner], two Jewish people who were both persecuted during the Holocaust,” Snyder said.

“They are extremely rare because, somehow, these photographs were produced in a place that had extreme deprivation. Also unusual is how the photographs survived once they were sent to Paulette, who, herself, was likely in hiding during the Holocaust. We have no idea how these rare images survived, which, if Paulette had been discovered to possess, would have easily given her away as a Jew.”

As the survivor generation passes, the museum is in a race against time to rescue the evidence of the Holocaust — archives, documents, photographs, videos, and artifacts — to help better understand this history and to bring its lessons to future generations. With the window of opportunity in collecting these fragile materials closing, the museum has intensified its efforts, actively collecting in 50 countries on six continents, in order to build the authoritative collection of record on the Holocaust and making it fully accessible and preserved for future education, research, and scholarship. To date, the museum holds more than 114,116 historical photographs and images, of which more than 34,874 are available on the museum’s website.

“Because Covid forced the world to stop and regroup these past two years, one of the things that organically occurred was the desire to organize and assess our futures,” Snyder said. “For many, this resulted in people pulling out Holocaust-era artifacts that they have held on to, contacting the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum and starting the conversation to donate.”

About David Semmel’s Collection

A third of the collection, originally owned by Paulette Getter, includes artifacts from early 20th Century Galicia, the pre-war region that straddled the modern-day border of southern Poland and western Ukraine. Another third covers pre-war France, and the remaining items are split among the post-war life in England, France and the United States.

Family photographs in the collection include Joachim “Muni” Getter; his first wife Chaya Silberman (David Semmel’s grandfather’s sister), and their teenage daughter Florine. As with Salomon and Paulette, the Getters, too, came from the Polish town of Przemyśl. In 1942, Chaya and Muni (along with Muni’s brother Aron and his wife Esther) were rounded up by the French collaborationist regime and sent to Auschwitz. All but Muni were murdered soon after arrival. Muni survived after being transferred to a forced labor camp at Mauthausen in Austria. Florine survived the Holocaust hidden in a convent in the south of France.

Paulette and Salomon were married high school sweethearts from Przemyśl. In addition to dozens of photos of the couple dating back to their teen years, she had kept four photos from him, taken when he was detained from a French detention camp, as well as a handwritten card in French (“Pour ma chère Paulette”). He was deported to Auschwitz and killed there. It is not known how or where Paulette survived the Holocaust.

After the war, Muni returned to Paris and found Florine, who went to live with David Semmel’s mother and grandparents in New York. Muni, Chaya’s widower, married Paulette, Salomon’s widow, in 1950 in Paris, then emigrated to America. Muni died in 1973. Paulette died a decade later. Florine Getter married Martin Sporn, also a Holocaust survivor. She passed away in 2004.

About the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

A federally chartered, nonpartisan educational institution, the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum serves as America’s national memorial to the victims of the Holocaust.

The museum is dedicated to ensuring the permanence of Holocaust memory, understanding, and relevance and inspires leaders and individuals worldwide to confront hatred, prevent genocide, and promote human dignity.

For more information, visit ushmm.org.

ᐧ