|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

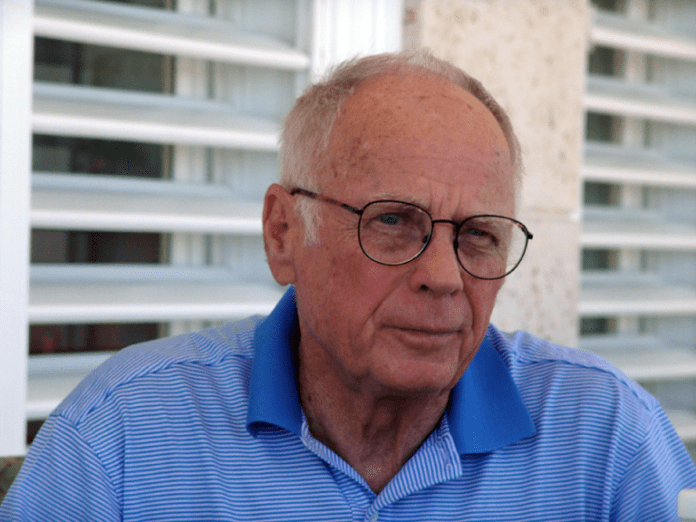

By a twist of fate, Miami native David Pearson — then a Peace Corps press officer, later the founder of a South Florida public relations and marketing firm — was called to help at the White House. Here are his observations, first published in 1966.

She is standing there in that funny posture of hers. Feet slightly apart, arms out from her sides, body tilted forward. Eyes so wide that she looks like one of those Keane paintings, hollow brown eyes fixed on the casket. Unseeing.

She still wears the nubby rose suit, chocolate-colored stains on her skirt where his head has lain.

Right now, in a mixture of dawn and candlelight, this woman I see is not regal or stoic or even in control. She is a grieving young widow bereft of her young husband, and as human as any deeply loving wife. Minutes later she will be sobbing bitterly, slumped in the arms of her brother-in-law, Bobby.

The world doesn’t think of Mrs. John Fitzgerald Kennedy this way. Her collapse by the coffin that night of the murder is but part of the never-before-told story of what really went on inside the White House in those tense, strange hours after sunset on Nov. 22, 1963.

I was there. I tacked black crepe. I fetched sandwiches. I wrote press releases. I emptied ash trays. I ran errands. I also watched and I listened. And I remember what has now become history and legend.

Who was I … and why was I there? I was a second-level Peace Corps press officer working for Sargent Shriver, and because the White House press staffers were all out of town – Pierre Salinger was flying over the Pacific with some Cabinet members; Mac Kilduff had gone with President Kennedy to Dallas and Andy Hatcher was out of reach – I was tapped to be inside the White House all through that remarkable night.

It is 3 p.m. that windy, fateful day. I am frozen at my desk, still stunned with the awful news of John Kennedy’s murder in Dallas. My phone rings.

“Shriver wants you and Lloyd Wright to go to Ralph Dungan’s office at the White House to help.”

Running all the way, we are across Lafayette Square and there in four minutes.

When I get to the front gates, I realize I don’t have my wallet with my ID card. Lloyd pulls his ID card out and vouches for me. Shriver has phoned ahead, so they let us through. I am surprised because the Secret Service men are running around like squirrels under the trees, and it occurs to me that they are jumpy for nothing.

Their president has already been shot.

We slip into Dungan’s big office. Seated around the large desk are Shriver; McGeorge Bundy; Arthur Schlesinger Jr.; Angier Biddle Duke; Capt. Tazewell Shepard (the naval aide); Maj. Gen. Chester V. Clifton (the military aide) and an Army protocol colonel. Duke has a protocol assistant who looks like Bruce Bennett, and I wonder what he is doing here.

Also present are John Bailey, the national Democratic chairman; Ted Sorensen and Lee White. Each will play an important role tonight.

The mountains of news accounts of those dark days will tell the world that Jacqueline Kennedy, who “has borne herself with the valor of a queen in a Greek tragedy, “as The Washington Star’s Mary McGrory would write, made virtually all the arrangements and that the widow “overwhelmed White House aides with her meticulous attention to the melancholy arrangements that have had to be made.”

Life magazine, in banner-headline fashion, would report that “Mrs. Kennedy’s decisions shaped all the solemn pageantry” and would go on to tell its readers that the widow arrived back at the White House at the crack of dawn to personally supervise the arrangements.

For the sake of American legendry it may be just as well for history to continue with this version. One of the requirements of a legend, after all, is that there be as few players as possible to accomplish whatever extra-human deeds need to be done. But it is not a true picture. What my eyes and ears take in tonight is a combined effort by a group of men —men who don’t always appreciate each other’s offerings, but men who get things done.

It is entirely true that Mrs. Kennedy would impart a number of thoughts and wishes, relayed from Bobby Kennedy to Shriver through continual telephone calls. But it would become clear to us on this sleepless night that the careful details are being accomplished by Shriver and certain other key men who translate her wishes into substance, form and effective action.

I look at these other men, these famous men who knew Kennedy intimately. I am distressed that I keep noticing Schlesinger’s crooked bow tie that proves he tied it himself, his baggy suit, the striped shirt. He looks just like an active historian. And the brilliant McGeorge Bundy (born on Monday, christened on Tuesday, Harvard on Wednesday, etc.), crisp and nasal.

Sleek in an Italian suit with slash pockets, no belt, no cuffs, pointy black shoes and cheap plastic glasses, he has to go soon. He is the White House civilian who must make sure no wrong military word gets out to all those Polaris submarines with the nuclear weapons pointed up.

When the president’s jet arrives at 5:58 p.m., Shriver has a long phone conversation with Bobby.

Then he turns and says to us, “I’d like you all to know, in a general way, what Mrs. Kennedy’s and the family’s wishes are. Mrs. Kennedy feels that, above all, those arrangements should be made to provide great dignity for the president. He should be buried as a president and a former naval officer rather than as a Kennedy.”

The man is kind and informal, but thoroughly decisive. The Catholic hierarchy at this point want a solemn high requiem Mass. Shriver explains respectfully that Kennedy didn’t like pomp. He presses for a pontifical requiem Mass, a “low” Mass with restraint, yet one given considerable dignity because it is the Pope’s Mass.

Like most men in important positions, Shriver frequently turns to trusted aides for information or opinions, even when qualified specialists might be at hand. Now Shriver speaks to a young psychiatrist, Dr. Joseph English, a close friend who is also a knowledgeable Catholic layman.

English’s gentle humor is a tonic: “Let’s take the low road, Sarge, “he says softly.

Shriver decides. “Look, if he made it a point to attend a low Mass himself every Sunday, why should we force a high Mass on him now?”

It is a question that calls for no answer. There is none. It will be a low Mass.

I realize now, in the brief silence that follows, that the real protagonist in all this planning is a man who says nothing, John Kennedy. Once the over-all schedule is worked out, it now becomes necessary to tackle the task everyone dreads. Who will be invited? Who are the most honored men in our nation?

And who are the president’s real friends?

While reading the draft of a press release, Shriver suddenly looks up. “Good Lord, we have forgotten Ike, Hoover and Truman.”

Shriver quickly jots their names down on the release and turns to Averill Harriman, who is slumped down next to me on a couch. I look at Harriman, at the deep, sad lines in his face. He is surprisingly tall, but thin and somewhat stooped.

“Mr. Ambassador, aren’t you a good friend of President Truman’s?”

Harriman nods. “Yes.”

“Would you please contact President Truman, President Eisenhower and President Hoover and invite them to come tomorrow morning?”

Harriman goes off to make and send the telegrams and returns two hours later to report that Truman and Eisenhower will be there, but Hoover’s health will prevent him from attending.

Shriver is, without question, the dominant figure here. Yet when a national magazine is later to publish a detailed account of his life, there will be not even a hint of what should go down as one of the most superb contributions of his career.

The plain truth is that he is more creative than the professionals tonight, more creative than the protocol experts, the clergy, the military and more creative than Andy Hatcher, Lloyd Wright or me with the press.

Adlai Stevenson has just walked in. He is rumpled and pale, more grief-stricken than anyone I have yet seen. He was in Dallas a few weeks ago, was spit on and hit by “hate” placards. But he’s alive, and he seems almost apologetic about it. He makes the rounds of the room slowly, speaking to every person, shaking hands.

Some say, “Hello, Ambassador, “ others, like Shriver, greet him with, “Hello, Governor.” He moves to the worn leather couch, sits next to me, and listens for a while. Hearing nothing he wants or needs to hear, he rises slowly with a great sigh and leaves the White House for some less public place of mourning. Throughout the evening the nation’s highest public servants continue to check in at the Shriver command post.

John Kenneth Galbraith moves in awkwardly, on legs as long as stilts. He talks in low tones to a few people, sits briefly, then, like Stevenson before him, senses his duty does not lie here and slips away.

Young Bill Moyers, officially Shriver’s deputy but actually the strongest link between the two presidential camps, confers with Shriver several times. Mike Mansfield worries through the room and disappears.

Everett McKinley Dirksen flows in, greeting the workers with mellow words: “I still can’t believe it has happened; I am stunned, shaken. But thank God there are those like you who are carrying the burden at this terrible time. Is there anything at all I can do to help?”

Somehow everyone feels a little better for Dirksen’s words.

Dungan’s secretary, honey-blond Pat Pepperin, has herded three other secretaries into the outer office, and they are typing up lists of people to be considered. Hundreds and hundreds of names. They are handled quickly, mostly read aloud by Dungan.

“Barney Ross, “Dungan says.

Someone answers, “Yes.”

So Ross, an old shipmate on the PT-109 and now a minor government jobholder, will be sent a telegram tonight. But for every yes, there are to be a hundred no’s. In addition to the names on the lists, other people throw in names.

In the middle of the long chore, Lloyd Wright says: “How about Billy Graham?”

There is a pause and Wright adds, “Billy considers himself a close friend of the president.”

Another short pause. By now there is real embarrassment in the air. Someone says Graham sometimes played golf with Jack Kennedy.

Dungan says simply, “No.”

Shriver says nothing.

Next name.

Dungan has the main say-so. He knows more than anyone else whom the president really liked. This is the final test.

Someone mentions George Smathers. Dungan says: “He’s a senator, isn’t he? Let him come with the rest of the senators.”

Yet Byron (Whizzer) White is invited even though he would also be invited separately with the Supreme Court justices.

They aren’t all in Who’s Who. Some are simply little people the president was drawn to. Like Roy Hoopes, a freelance writer and work-up softball player.

John Bailey, chairman of the Democratic National Committee, keeps throwing up names of old-line pols, people Bailey thinks Kennedy is indebted to because of their help in past campaigns.

Finally Shriver cuts him off. Looking Bailey straight in the eye, he says, “John, we are not trying to return political favors here tonight. We are trying to ask only those people who we know were personal friends of the president.”

Bailey only blinks and continues to baldly suggest names of political cronies from New England.

Bailey: An angry uncle, rumpled and tired, totally out of place, actively incongruous. A magical facility for saying wrong things at right times.

Shriver remembers that he has called Bill Walton, an artist and close friend of the Kennedys, and asked him to come over. Walton, along with the presidential arts advisor, Dick Goodwin, is preparing the East Room. Shriver asks me to go over and get Walton to see if he knows of any Kennedy friends who might have been left out.

I have never been through the inner rooms of the White House, but somehow, I guess it must be from seeing the White House on TV and in pictures, I walk through the many corridors directly to the East Room.

Walton, natty and urbane, is quietly giving instructions to a furniture upholsterer who is up on a 20-foot ladder, hanging black window curtains. Walton belongs at a Palm Beach garden party, not in the White House on this blustery November night. Blue blazer, striped tie, flannel pants and polished loafers. Absolutely cool.

Talking with him as we go from the East Room back to Dungan’s office, I am amazed at Walton’s poise. I know he is very close to the president, and especially to Mrs. Kennedy. It strikes me again that these people for whom Kennedy had such high respect are acting just as he would have wished them to. They have an almost superhuman ability to remain in complete control … emotions sheathed … fine and gentle humor … restraint.

At about 1 a.m. Shriver heads over to the East Room for the first time, followed by Lloyd Wright and me. On the way through the hollow corridors we pass an open room with a TV set turned on. No one is in the room. The network is running tapes of old Kennedy speeches.

Shriver walks into the room, impulsively sits down before the TV set, looks at the screen. It is JFK’s moving Berlin speech. Kennedy says, “Ich bin ein Berliner.” The German crowds roar. Shriver gets up, walks out, heading again for the East Room. After a few stops he comes to the president’s office, where an armed Marine guard stands by the open door. There is a chain across the opening to the darkened room.

Shriver stops at the chain and looks in. The Marine guard flicks on the light. Shriver stares at the president’s empty chair a full minute, then turns and starts to say something to us. All that comes out is a hoarse croak. It is the first time I have seen any visible sign of the deep distress that must be tearing at him.

He quickly turns on his heel and marches down the corridor to the East Room, clearing his throat, squaring his shoulders and staying several paces ahead of us.

I see Bill Walton lighting a cigarette. I walk over and borrow his lighter. Walton tells me of Jackie’s request: “She wants the East Room to be prepared for him like it was for Lincoln. If they’re going to get here about 2:30, I really doubt that we can match the Lincoln scene by then.”

Now, and contrary to later press versions, Walton, Goodwin and Shriver decide not to try to recreate the Lincoln decor exactly. It is felt that heavy black curtains over all the mirrors and crepe drooping over all the chandeliers would make the room too morose and too dark.

Walton and Goodwin are studying an engraving of Lincoln lying in state in the East Room, an illustration in the White House guidebook. “They were pretty rococo in those days,” Goodwin says.

“I think we can capture the right feeling,” Walton suggests, “and yet adapt it a little more to Jack Kennedy.”

So they simply hint at mourning, draping only the mirror frames with crepe, looping only a single strand of crepe around the center of the chandeliers.

I say hesitantly to Walton, “Maybe there ought to be some kind of crucifix.”

Joe English agrees. A crucifix is sent for, and when it arrives, it turns out to be pretty awful, with a bloody corpus.

Shriver takes one look at it and says, “That’s terrible. Go get the one in my bedroom.”

So we get the Danish modern crucifix from Shriver’s home in suburban Maryland. I ask Walton whether the casket will be open at any point. He says softly, “Jack didn’t like to be touched. I doubt whether he’d like to be stared at now.”

About this time Mac Kilduff, the assistant press secretary who came back with the body on Air Force One, arrives. There is a pause in the preparations while Kilduff gives us a rundown on the events in Dallas. It is the first time I hear that Jackie’s pink suit as well as her stockings were splattered with blood.

As the time for the body to arrive nears —it is now scheduled for 4:30 a.m. —Shriver’s desire that everything be right extends outside of the East Room to the hall and entranceway. He has to move furniture from the entrance to make sure there will be room for the pallbearers to bring in the casket. We have already moved a large grand piano out of the East Room, the same piano that was used for several of the Kennedys’ musicales.

Pierre Salinger has arrived in Washington and is sitting in his office with his feet up on his desk, a cigar clamped between his teeth, talking to Kilduff and Hatcher, his two assistants.

Now, in the blackest part of the night, just before dawn, headlights begin to cut through the gloom in front of the White House. Most of us, embarrassed and feeling out of place, retreat to a corner of the East Room. Shriver remains at the door to greet the widow and direct the pallbearers.

I hear the routine sound of doors opening and closing, low voices; then come sounds that make me shiver. A military voice snaps a “march” command; there is the clipped staccato sound of boots hitting the hard floors. We’ve been in this hushed and calm house for hours, and now I hear marching.

The Norman Rockwell Marines carry in the body and set it down on the replica of Lincoln’s catafalque. The young priest and two altar boys kneel and pray silently. The pallbearers step back from the casket.

There is a short pause; no one quite knows what to do first. There has been no rehearsal. No one has had any experience. What do you do when you bring a dead president into the East Room of the White House at 4:30 in the morning?

The priest walks to the head of the casket, carrying holy water in a tiny one-ounce bottle. He says a couple of prayers in Latin and in English and sprinkles a few drops on the bier.

Right in the doorway stands Jackie, with Robert McNamara on her right and Bobby Kennedy on her left. I didn’t know McNamara was that close a friend. What a fierce black eagle in a dark suit, his mouth a straight line above the flexing jaw. And still he is tender and solicitous of the widow.

Over to Bobby, stooped and questioning, kind of the way Montgomery Clift used to look. His suit hangs unpressed, his knot off to one side. Stunned, caught out sleep-walking in hell. Will he wake up, will we, and find everything’s all right again?

The little altar boy with a candle lighter goes up to ignite the four large candles at the corners of the casket. The wick at the first candle is down under the metal shield; it seems to take him an excruciatingly long time to light the candles. I should run and pull the wick up. I know Bobby Kennedy, another ex-altar boy, has the same thought. But who could go up and ruin the scene?

So we wait.

Now I look over at Jacqueline Kennedy, and it seems to me that she appeared out of nowhere, an apparition standing in that characteristic pose of hers that would become so well-known to the world in the ensuing days.

Feet apart, the slight lean forward. Stiff and awe-struck. Her lips are parted slightly. Her eyes are as if she had just been surprised, only they stay that way. A wrinkle of disbelief on her brow.

I look at her suit. I remember what Kilduff has said and am surprised that she hasn’t changed clothes. The dark stains are all over her skirt and her stockings. I know it doesn’t matter that she hasn’t changed her clothes, but the idea gnaws at me, and it is another one of the totally irrelevant thoughts that plague us all through the night.

This acute sense of awareness is heightened, I suppose, by countless cups of coffee and nerve ends that are strung up like guitar strings. I think I know what an LSD trip must be like, with the intense feeling of reality. In fact, the little boy lighting the candles might be taking much less time than I think.

The candles don’t smoke. Very expensive beeswax.

The priest moves back. He nods to Mrs. Kennedy. She takes the five steps to the casket and quickly kneels down, almost falling, on the edge of the catafalque. Her hands hang loosely at her sides. She lays her forehead against the side of the casket.

She kneels there like that for what seems a long time, but it must span no more than two or three minutes. There is dead silence. Absolutely no sound of any kind. The only movement is the dancing of the four yellow flames. The soldiers are statues. The rest of us, motionless, blend into the darkness as if not there.

I am almost afraid to breathe.

With her forehead tilted onto the casket, the widow seems like a teenage girl, head against the flank of her horse or something equally dear. And equally mute. She picks up the edge of the flag and kisses it.

Slowly, she starts to rise. Then, without any warning, Mrs. Kennedy begins crying. Her slender frame is rocked by sobs, and she slumps back down. Her knees give way. Bobby Kennedy moves up quickly, puts one arm around her waist. He stands there with her a moment and just lets her cry.

It is a perfectly natural thing for a woman to do. It would only be later, when the world is to perceive her as a regal and strong and almost inhumanly stoic, that I will relive this scene.

Here, by her husband’s casket, she is most human; she is grieving; she is wretched. Through the coming days many people would actually wonder whether she could have loved him very much because she didn’t seem to mourn the way people mourn who love deeply.

But those of us in the East Room tonight know she did.

Bobby moves her away from the casket. She is led upstairs. They have brought John Kennedy home.

David Pearson lives in Coral Gables, Florida. He can be reached at david@davidpearsonassociates.com.