Jack Black was standing in the dark-green, jungle-like backyard of South Miami Mayor Philip Stoddard. The actor gazed at the blue-black pond with its prowling bass and sunfish, then up at the roof. Gleaming white solar panels, the slender, geeky Stoddard explained, power his whole house, including air conditioning and even an electric car. He pays Florida Power & Light less than $10 per month.

Surrounded by three cameras and mikes and dressed in a button-up, short-sleeve shirt and khakis, Stoddard was holding a cylindrical piece of holey limestone. He pushed a yellow pencil through one of the holes. “So, Jack, this is the reason we can’t keep water out,” the 59-year-old said in an effort to explain why building walls wouldn’t stop sea-level rise from inundating Miami.

The comedic actor — with a billowing orange T-shirt and piercing, catlike eyes — spoke in various tones, from somber to comic, trying out the proper inflection.

Finally, as Black’s personal assistant scrambled to keep Stoddard’s noisy dog, Sparrow, away from the mikes, the comedian settled on a slightly sarcastic tone: “So this is the foundation Miami is built on?”

“You got it,” Stoddard said.

The mayor then pointed toward the dazzling panels on his west-sloping roof and explained they counter climate change and deprive FPL of revenue. He gleefully described a recent electric bill for $9.41. “It’s so much fun!”

Black’s reaction was swift, wide-eyed, and completely lacking in the former Kung Fu Panda’s usual verbosity: “Wow.”

Black was filming an episode of Years of Living Dangerously, an environmental series for National Geographic that was broadcast this past November. He sought out Stoddard for the same reason Rolling Stone, NPR, the New York Times, the Guardian, and many others have in the past few years: The mayor and Florida International University biology professor pulls no punches in describing the environmental disaster that awaits Miami — and how big corporations, particularly FPL, contribute to the problem.

His assessment of the utility company: “An evil genius.”

For years, Stoddard has railed against FPL’s nuclear reactors at Turkey Point, led the charge to stop new transmission lines in South Miami-Dade, and vehemently opposed the power company’s $22 million campaign for a duplicitous amendment to the Florida Constitution that was sold to voters as pro-solar power but really aimed to crush it.

He’s pointed out that FPL has long had the state’s politicians in its pocket, shelling out $8 million to them directly last year and another $8 million in pushing the anti-solar amendment. And he’s said that Gov. Rick Scott has packed the Public Service Commission (PSC), the regulatory body that generally rubber-stamps FPL demands, with utility lovers.

“FPL has bought political control of the Legislature, the Cabinet, and the PSC,” Stoddard says. “It throws corporate money against any candidate who doesn’t toe their line.”

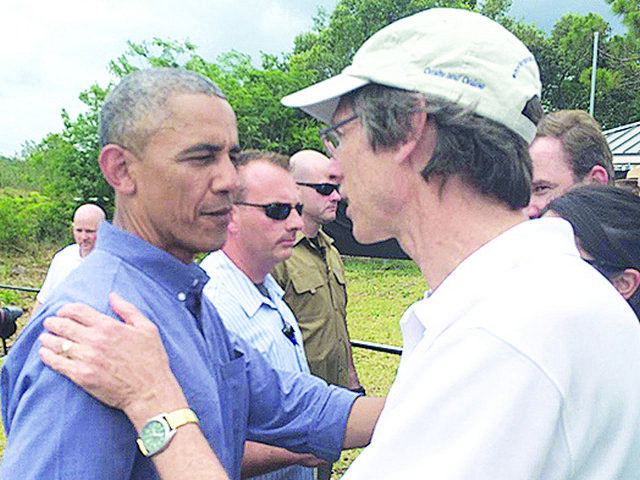

In this era of polarized politics, his star has skyrocketed nationally. He appeared via video at the Democratic National Convention last July warning of sea-level rise. When Barack Obama toured the Everglades, Stoddard was there to say Turkey Point could destroy the national park. Such efforts caused Politico to name him one of the top 50 “thinkers, doers, and visionaries transforming American politics in 2016.”

It’s the solar issue that has consumed Stoddard of late. He told Hialeah schoolkids it is the best way to combat global warming, and he’s working with an energy fund to get lower group rates for all Miami-Dade residents. He believes solar power is crucial to combating the sea-level rise that endangers South Florida. “Nuclear is dying of excessive costs,” he says. “Utilities are deathly afraid of rooftop solar because residential customers are their cash cow.”

Because of its political power, FPL has been able to prevent corporate competitors from providing solar, wind, and other kinds of energy in Florida.

Susan Glickman, Florida director of the Southern Alliance for Clean Energy Action Fund, an advocacy group, says the Sunshine State is one of only four states (along with Kentucky, North Carolina, and Oklahoma) “where the law prohibits anyone other than your government-assigned monopoly utility from selling electricity — solar or otherwise.”

In such a controlled environment, Stoddard presents a real threat, Glickman says. “As an elected official, he’s FPL’s worst nightmare,” she says. “He’s also a scientist who can go toe-to-toe with them on the technical arguments.”

Over the years, FPL has staunchly defended itself: Its nuclear reactors and transmission lines are safe and don’t harm the environment; it’s in favor of renewable energy as long as it’s not a burden on customers. Its charges are fair, and its average electric bill is the lowest of all utilities in Florida — 30 percent below the national average.

New Times submitted a list of more than 20 detailed questions to FPL, including what the company thinks of Stoddard. Spokesman Bill Orlove refused to answer any of them. “We’re not going to participate,” he said.

Stoddard grew up on the outskirts of Washington, D.C., and majored in biology at the liberal Swarthmore College. He worked a bit for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, earned a PhD in animal psychology at the University of Washington, and then did a postdoctorate in neurobiology and behavior at Cornell University. He came to FIU in 1993, where he’s specialized in animal communication, beginning with birds and then moving to fish.

In 1994, he met Gray Read, a slender, bespectacled nerd with light-brown hair, three and a half years his senior. From Philadelphia, Read was a doctoral candidate at the University of Pennsylvania recovering from a divorce when she and Stoddard were set up on a blind date at a Japanese restaurant. He showed up in a 28-year-old Volvo he called Penelope. His pickup line: “Ever seen an alligator?” She was amazed: “How can you resist a line like that?” Their second date was a sunset picnic in Shark Valley. “We didn’t get home till 3 a.m.” They married in 1998.

Stoddard entered the battle against FPL in 2009. He soon realized the central problem was Turkey Point — and FPL’s plan to build two more nuclear reactors there. Power would be transmitted northward by two new, huge transmission lines, with towers of 80 to 150 feet, one running roughly along South Dixie Highway, the other on the edge of the Everglades.

So Stoddard started popping up at town-hall meetings, at government hearings, and on editorial pages with letters to the editor.

“Crazy,” he called the idea of a nuclear plant on the edge of the ocean, between Biscayne and Everglades National Parks, especially with the coming sea-level rise.

He decried the cooling canals that were way too hot — up to 104 degrees — creating algae plumes and pushing saltwater into the South Miami-Dade well fields that provide drinking water.

He thought it stupid to spend $20 billion for new reactors when “this money could fund solar/wind renewable energy at $25,000 per household with no new power lines.”

Within months of the outset of this campaign, he says, his neighbors “snookered” him into running for mayor of South Miami, a mixed-income city of 12,000 where 20 percent live below the poverty line. He filed in 2010, 30 minutes before the deadline.

The town was in turmoil. City Manager Ajibola Balogun and City Attorney Luis Figueredo had been abruptly fired. Commissioner Jay Beckman had been murdered by his 17-year-old son with a shotgun blast to the face. Mayor Horace Feliu was known for getting in shouting matches with residents.

When it was revealed that Feliu, running for re-election, had once endorsed the new FPL transmission lines, Stoddard was “appalled,” he says.

Stoddard garnered 59 percent of the vote, winning a position that pays $14,000 per year (though “FIU cuts my pay 10 percent to let me do my job [as mayor],” he says).

He quickly found the press and the public paying much more attention to him. “I’ve been saying the same things as a scientist for years and nobody bothered to put it in the paper. You have ‘mayor’ in front of your name, it becomes newsworthy.”

Harold Wanless, a University of Miami professor and Stoddard colleague in the environmental wars, points out that many mayors worry that statements on climate change could endanger property values. But, he says, Stoddard has no such compunction. “Phil is not afraid to be totally outspoken.”

At an early commission meeting where an FPL manager appeared to defend transmission lines, Stoddard told him: “I’m going to fight you to the mat.”

He also extended his battleground to the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC), complaining about 2 million pounds of spent radioactive fuel rods stored on the nuclear site in South Miami-Dade, where they might reside for centuries. “FPL has been playing a game of chicken with the NRC,” he exclaimed, adding that the NRC invariably agrees with the utility.

Stoddard, who gives out his cell-phone number to all residents, was easily re-elected in 2012, but by the 2014 ballot, it appeared FPL was fed up.

South Miami residents, accustomed to talk of parks and city-hall remodeling, were subjected to a telephone push poll that reeked of dirty politics: “Would you be more or less likely to vote for someone who had been reported to the Florida Child Abuse Hotline for being naked in front of two unrelated teenage females in their home?” they were asked.

That was a clear reference to a 2011 incident that Stoddard says was nothing more than confusion. One night, his daughter and a female exchange student were sleeping in his home when there was some sort of noise. The exchange student screamed something about an intruder. Stoddard — who sleeps in the nude — immediately jumped up to investigate. South Miami Police were also called to search for a possible intruder.

There was no call to a hotline. It was all described in a police report. No charges were ever filed.

Miami Herald reporters Christina Veiga and Alex Butler reported that the push-poll phone call ended with a message that it was paid for by Progress for the People.

Records showed that the group had raised $5,500, most of it from Homestead-Miami Speedway — 24 miles outside South Miami city limits.

The reporters stated both the speedway and FPL shared a lobbyist — Jorge Luis Lopez, who was involved in another political fundraising organization, to which FPL had donated $15,000. County records show Lopez has been a lobbyist for FPL in Miami-Dade since 1998.

Both Lopez and FPL told the Herald the utility had nothing to do with the push poll.

Stoddard says he uncovered other FPL-related funds used in the campaign against him — “money that came out of a dark closet, illegal money… It backfired. People were disgusted by it.” He won 62 percent of the vote, beating Valerie Newman and Rodney Williams.

Meanwhile, FPL was chalking up its own victories. In May 2014, Governor Scott and the Florida Cabinet approved the utility company’s request to build the new reactors and 88 miles of transmission lines. In response, the City of Miami and other South Miami-Dade towns joined South Miami in a lawsuit that aimed to overturn the Cabinet’s decision.

Stoddard had new allies.

That same year, the NRC formally stated the cooling canals’ temperature could rise to 104 degrees without harming the environment. And state regulators approved a ten-year plan to fix the Turkey Point canals. The company claimed this would stop the spread of algae as well as saltwater intrusion in the well fields that provide the county’s drinking water.

Stoddard fought back at the federal level, charging that FPL had “totally ignored any realistic sea-level rise” estimates in its plans. He added that the company’s customers would end up paying billions if Turkey Point had to be eventually abandoned.

In fact, customers have already paid more than $250 million for the new reactors. Breaking from its own longtime rules, the PSC rubber-stamped an FPL request in 2011 that forces customers to pay the utility for development of the new reactors before they are finished. “FPL is trying to save money for themselves but push the cost on us,” Stoddard complains.

In 2015, little South Miami agreed to pay $13,000 to join the City of Miami and the Village of Pinecrest to hire an economist to provide data to pressure the PSC to no longer make customers pay in advance for the reactors.

That effort went nowhere, but then FPL hit a series of roadblocks. In February 2016, a Tallahassee administrative judge rejected the plan for fixing the cooling canals. Two months later, a state appeals court threw out the Cabinet’s approval of the new nuclear reactors and the power lines — saying, among other things, that Scott and company had ignored local development regulations and effects on wildlife and the Everglades.

FPL responded in May by announcing it would postpone plans for the reactors by at least four years.

Stoddard understood. “The cost [of nuclear] has more than tripled… Meanwhile, the cost of solar has fallen like a rock,” he says.

Still, FPL vowed to continue seeking approval for the new reactors. In November, the NRC came through. In a 1,200-page review that ignored warnings of sea-level rise and the ongoing problems with the cooling canals, the NRC said there were no environmental issues blocking the two new reactors.

Stoddard wasn’t surprised. “The NRC exists to protect the nuclear industry from itself; they’re not here to protect the public. If there was no nuclear, then all the guys at the NRC [would] lose their jobs.”

“What propelled me to international fame overnight was the Guardian,” Stoddard says one evening sitting on his lush back patio.

In 2014, he explains, a reporter for the British newspaper/website asked him about Sen. Marco Rubio’s claim that climate change wasn’t caused by humans. “Rubio is an idiot,” Stoddard replied.

Soon reporters barraged him, seeking withering quotes about Rubio and other climate-deniers. “I got calls from everybody from NBC to Al Jazeera, fascinated that someone would call out Marco Rubio for being a twit.”

The patio faces dense foliage, with a royal palm hovering over a sunken garden. The lake, fed by a well in the yard, is its own ecosystem: mosquito fish eat larvae; mollies and sunfish consume snails and algae. “We never feed the fish,” Stoddard says. “They take care of themselves.”

He sits beside his wife, Read, who’s now an associate professor of architecture at FIU. She shares Stoddard’s progressive views, frequently firing off letters to the editor. (“It’s increasingly clear that Trump supporters and now the whole country are victims of a con man,” she recently wrote in the Miami Herald.)

Stoddard and Read often aim to persuade younger people of their vision. “Young people don’t want to keep living in the suburbs,” Read says.

“They’re sick of it. They want to be able to walk to work — they want a social, urbane, stylish lifestyle.”

That’s good, she says, because the suburbs in the far south and west of the county sit so low geographically that there’s no protecting them from sea-level rise. “The suburbs are toast,” she says.

Their three-bedroom place (worth $530,000 on Zillow) is a basic tract house, though Read has opened it up inside for a large, flowing living space. Some years ago, they heeded an energy audit and added insulation, sealed ducts, fixed leaky spaces around doors and windows, installed double-paned glass doors, and bought a more energy-efficient air conditioner. That cut their monthly $125 electric bill in half.

In 2014, they went solar. It cost $16,375, which was reduced to $11,500 after they took advantage of a federal income tax deduction.

Their house uses net metering, which works like this: During the day, the solar panels generate far more electricity than the house uses. The excess flows into the FPL grid. At night, it reverses, the house using FPL power for lights and such.

One key problem: Stoddard pays FPL about three times per kilowatt-hour more than the company pays him. That tradeoff upsets environmentalists because it makes it more difficult for the homeowner to justify installation costs. In Maryland, Read’s cousins earn a premium of about $100 per month for providing power to the deregulated grid.

“Utilities will tell you it’s cloudy in Florida — solar doesn’t work,” Stoddard says, “but we were pushing so much power to the FPL grid and getting so little in return that we went out to buy an electric car to soak up the difference.”

That car, a Nissan Leaf (starting price $31,000, with a 107-mile range), is powered by the solar panels. Still, Stoddard and Read carpool when they can (their gas-guzzler is a Prius) and both frequently ride bikes, which provide great exercise but in South Florida are also a bit dangerous:

In 2011, a drooping bougainvillea forced Stoddard off a sidewalk. The crash fractured his hip and broke his helmet, causing a concussion.

Today only 11,000 Florida customers are hooked up to the electric grid via net metering, according to the PSC — a number so scant it seems hardly worth the attention of utilities. But the potential is huge. If half of Miami-Dade’s rooftops were converted to solar, Read estimates, they could provide as much as half of all the county’s energy needs — including cars and cruise ships.

That possibility is a long way off, of course. But the power industry is keenly aware of the threat. Its trade association, the Edison Electric Institute (EEI), issued a report in 2013 called Disruptive Challenges — meaning solar and other alternatives — which foresaw an ominous future for investor-owned utilities if there are more customers like Stoddard.

“Customers are not precluded from leaving the system entirely if a more cost-competitive alternative is available such as solar and improved batteries,” the report said. Utilities would have to respond by raising rates for those customers who remain.

That would create a “vicious cycle,” the EEI concluded. The Wall Street Daily and other publications dubbed this concept “a death spiral.”

It’s this conundrum that pushed FPL and other utilities into spending more than $20 million to back the anti-solar Amendment 1 last year.

The measure acknowledged Floridians have a right to own solar equipment but added that nonsolar customers “are not required to subsidize the costs of backup power and electric grid access to those who do.”

The implication: Solar customers would be penalized rather than rewarded.

Stoddard and many other environmentalists believe utilities planned to use the amendment to kill net metering — or require solar owners to pay utilities for using solar — on the theory that solar customers unfairly avoided paying their share for the transmission lines.

As Stoddard wrote in a letter to the Herald last year: “Our rooftop solar system is actually subsidizing poor customers. How? Our west-facing roof exposure pushes extra power onto the grid during peak load time, which saves FPL customers the extra cost of buying power from peak generators [which kick in when power demands are greatest] while cutting carbon emissions.”

In the city-owned Milander Center for Arts & Entertainment across the street from Hialeah High School, Stoddard and four other FIU professors sit side-by-side onstage at a table draped in black cloth. In the audience are some 80 students, hunched forward, some with notebooks on their laps.

The professors are telling about the dangers of sea-level rise and the need to push both politicians and their parents to support solar.

“Your knowledge is going to move the political process down here,” says Stoddard, dressed in a navy blazer, light-blue shirt, blue striped tie, and khaki pants. “As mayor, I’m responsible for people’s welfare. They look at me as the adult in the room. The Legislature, the U.S. Congress are not. I mean, we just elected a president who doesn’t get it either.” Many of the students giggle. “So it stops with us. We’re it.”

Most of these students understand the danger.

“I live right next to a canal,” says Pedro Peña, a square-jawed linebacker type from Hialeah Educational Academy. “We know it can hit us fast.”

Stoddard asks the Hialeah kids what they expect: “How high can the water go and you be able to live here?… It’s likely to be in your lifetimes that your ability to stay in this community is going to be challenged… Hialeah has a lot of low areas.”

Then he grabs their attention with a phenomenon that’s now challenging South Miamians.

“You know the first thing that fails when the water comes up?… If you’re on septic, which most of the county is, your toilet flushes into the bathtub.”

The students chuckle.

A few minutes later, he closes his pep talk: “Solar is doable,” he says. “So bug your parents — you’ve got to do this.”

Stoddard — like most Florida environmentalists — is feeling upbeat since the November defeat of Amendment 1.

California-based SolarCity, a $2 billion entity owned by Tesla’s Elon Musk, announced this past December that the amendment’s defeat prompted the company to decide the time was right to expand operations to Florida, beginning in the Orlando area. A news release noted that the Sunshine State “consistently ranks among the nation’s ten sunniest states” and thanked voters for rejecting “a cynical attempt by solar opponents.”

Nationally, things aren’t so rosy. President Donald Trump has promoted coal as a fuel. In 2012, he tweeted that climate change was a Chinese hoax. And minutes after he was inaugurated, the page on climate change was removed from the White House website.

Meanwhile, city and state governments near oceans — everywhere from California to South Miami — are realizing they can’t wait for the feds to act. They are moving on their own to combat climate change. As a recent New York Times op-ed piece noted: “Many of the planet’s cities lie along the coasts and are threatened by slowly rising seas. Seventy percent of those cities are already dealing with extreme weather like drought and flooding,” historian Jeff Biggers wrote. “It is obvious that city planners, mayors, and governors have had to re-envision how their cities generate energy.”

The latest example: This past December, the Miami-Dade County Commission passed 12-0 a resolution urging the Florida Legislature to amend laws so that the county could sell electricity from burning garbage or from solar panels to FPL at market rate.

Stoddard: “I’m going to ride the solar thing for a while. We’ve got to build on the Amendment 1 win — and do right by the planet.”

He expects FPL to push the Florida Legislature and the state’s Public Service Commission to find ways to punish solar users.

Such punishment might be approved in a state where (1) Gov. Rick Scott has prohibited agencies from even mentioning climate change; (2) the PSC recently dropped a requirement, similar to one enforced by most states, that utilities promote energy conservation; (3) there’s no goal to produce a certain amount of renewable energy by a certain date; and (4) the PSC recently handed FPL an $811 million rate increase.

The utility company, already enjoying a $1.6 billion annual profit, got a $400 million boost in January. And it will get another $411 million over the next three years. A customer using 1,000 kilowatt-hours a month is expected to pay $9.50 more per month through 2020 — beginning with $5-per-month bump this year.

The Sierra Club has asked the Florida Supreme Court to halt the rate increase:

“There’s absolutely no justification for making families and businesses pay more of our hard-earned money just so FPL can line its shareholders’ pockets and pollute our air and water in the process,” the advocacy group said in a news release.

Still, Stoddard sees a silver lining in the rate increase: “It’s going to push people to solar,” he says.

He says the approval of a solar amendment by 70 percent of voters last August was a “useful step” even though it gives a tax break only to property owners installing solar panels on commercial properties rather than homes.

Meanwhile, Stoddard and other environmentalists continue to battle FPL’s plans for deep-well injection of hot, salty water containing radioactive tritium. The utility claims the wastewater will end up far below the region’s drinking water wells. In a statement to the NRC, Stoddard called the deep-well plan “an environmental three-card Monte” that just keeps shifting the problems in ways that invariably backfire.

And nuclear plants continue to close. In 2013, Duke Energy shut down Crystal River, north of Tampa, because it needed expensive repairs.

California regulators have a commitment for the state’s last nuclear plant to shutter within the next decade. And in January, pressure from New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo caused a power company to agree to close a nuclear plant less than 30 miles from Manhattan within four years. “A ticking time bomb,” Cuomo called it.

That closing sounds like a good plan for Turkey Point, Stoddard says. “The sooner the better.”

After the story was published online at Miami New Times, Stoddard sent in an email expanding on several points in the story…

1. We had a home invasion burglary that morning in 2011. The burglar had removed several computers and had come back for more when he ran into our exchange student in the kitchen. He motioned her to be silent, but when he reached into his pocket she screamed to wake the dead (and me) and locked herself in the bathroom.

2. A used Nissan Leaf goes for less than $10k these days. We bought ours used.

3. A couple of weeks ago, I put a resolution before the Green Corridor board, to give a $75,000 grant to the Community Power Network / FL Sun to start solar buying co-operatives in Miami-Dade County. The resolution passed. Expect the cost of solar in Miami-Dade to drop even further.

Comments are closed.