A new app and website launched by an FIU alumnus is helping residents of Flint, Michigan, assess the risk of lead contamination in their homes and find resources to cope.

The Mywater-Flint app, designed by computer science alumnus Mark Allison Ph.D. ’14 in conjunction with his students at the University of Michigan-Flint, provides information on local pipe infrastructure, how to test water for lead, where to find clean water and more.

Flint faces an ongoing crisis of lead seeping into the city’s drinking water supply, which prompted former President Barack Obama to declare a state of emergency there in 2016. The Environmental Protection Agency considers 15 parts per billion (ppb) the limit for safe levels of lead in drinking water. Tests of homes in Flint have yielded 104 ppb, with some results as high as 13,200 ppb.

Allison, who earned a doctorate in computer science from FIU in 2014, joined the University of Michigan-Flint faculty two years ago. There, he teaches an experiential learning-based course that encourages students to use computer science to solve problems in the community.

“The thing about the Flint water crisis was that when it developed, there were several avenues of information, and a lot of misinformation,” Allison said, which sparked the idea for Mywater-Flint, a centralized database of resources and news for Flint residents.

“A lot of people didn’t actually understand what was going on. Some people thought you could boil water and get rid of the lead. That was not true. There was a real need for some kind of assistance, and the way I thought we could help was using software engineering.”

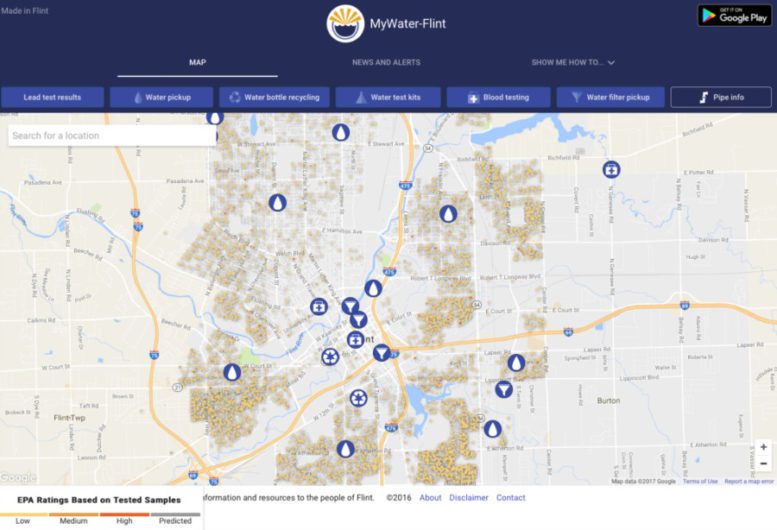

The app is set up as an interactive map. It is the first of its kind to use geolocation to direct citizens to the closest resources in their area, including water filter and testing pickup areas, pipeline information, blood testing and where to get clean water.

The app uses an algorithm to determine, if a home has not yet been tested for lead, the probability that it could be contaminated based on data from surrounding residences. It shows areas where work is being done to correct contamination and provides residents a timeline for when work on their homes will be completed.

“There’s been a complete erosion of trust between the citizenry and the decision-makers in Flint. This app, it doesn’t have a political agenda, so that’s what’s driving its impact,” Allison said.

Mywater-Flint also aggregates news and alerts on the water crisis, and features videos and instructions to help residents install water filters and use a water testing kit in their homes.

“The situation has been very politicized, so people have been very skeptical of how they get their news and where to get their support,” Allison said. “I think that’s one of the good things about the app.”

The work Allison and his students started soon attracted a partnership with Google, which funded the project and provided software engineering experts to work directly with his students during the design process.

“It gave the students real-world experience working with people in the top of the field,” Allison said.

An important feature of Mywater-Flint’s programming is the fact that it’s open source, meaning the app can be adapted for other cities if need arises.

“There have been other apps out there focusing on the health aspect of the crisis, etc.,” Allison said. “This one is unique.”

Mywater-Flint is available for Android smartphones and online at Mywater-Flint.com.