For more than 10 years, Garfield Jarrett proudly wore the uniform of a U.S. Marine. Military service was both his passion and his career. But injuries sustained during a 2008 roadside attack in Iraq ended it all.

Granted a medical discharge, Jarrett returned home to South Florida and enrolled at FIU to pursue a bachelor’s degree in social work. Driven by a desire to help others, Jarrett graduated and promptly started on a master’s degree in the same field. Yet he felt adrift in his new reality.

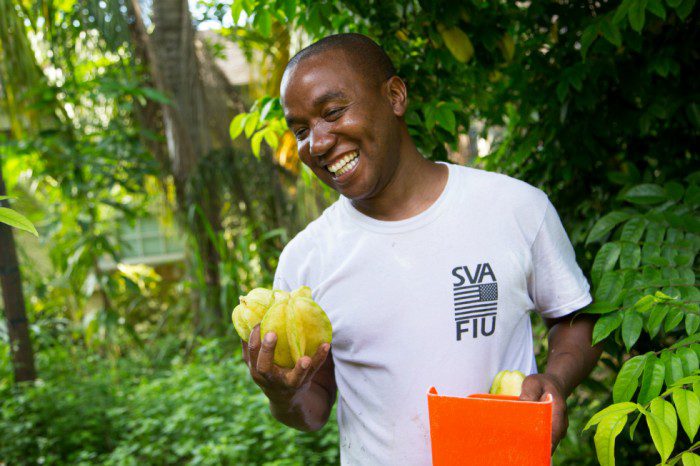

Then one day on campus, a flyer caught his attention. It announced a new agriculture program for military veterans. Suddenly, Jarrett’s aimlessness gave way to fond childhood memories of growing up on his grandfather’s sugarcane plantation in Jamaica. The possibilities brought a smile to his face.

A recognized need

Florida has large numbers of minority and new farmers. The most recent USDA Agricultural Census identified more than 10,000 operators as having farmed for less than 10 years, of which more than 4,000 are Hispanic and roughly 750 are women. The majority are located in South Florida and many, according to the Coalition of Florida Farmworkers Organizations, represent an emerging trend in Miami-Dade County: They are both farmworkers—that is, they labor for others who own land—as well as decision-making farmers, who lease land on the side to cultivate on their own as a means of supplementing income.

Separately, Florida has a growing population of recent veterans—some 200,000 have returned to or moved to the state since 2008, according to the U.S. Census—and the largest portion has made its home in Miami-Dade County. As many as 10 percent are currently unemployed.

Two professors in the Department of Earth and Environmentwithin the College of Arts & Sciences know the statistics well. Ten years ago, Krish Jayachandran and Mahadev Bhat founded FIU’s Agroecology Program, a research-based and experiential learning academic track geared to educating students to work at the U.S. Department of Agriculture and in related businesses. As the pair and their students took advantage of the living lab all around them—that is, the surrounding farm areas, including places such as Homestead and the Redland Agriculture Area, home of the nation’s winter vegetable garden—they began to see ripe possibilities.

The professors say, and local USDA officials concur, that plenty of individuals are willing and able to put in the time and effort required of such an endeavor, but they lack the means and knowledge to get up and running. Bhat and Jayachandran characterize the ramping up of even a small parcel as “a very complicated process.”

“It’s not just finding a piece of land and putting in plants. If you really want to make a living out of that you have to do it very systematically,” Bhat said. “You need all the resources that are required, including financial resources, and then you need to have the know how.”

The latter includes an understanding of local vegetation and growing seasons, soil and climate, pest control and irrigation, not to mention budgeting, planning, marketing and more. Daunting as all that might sound, the rewards are there for the motivated.

“Even with one acre in South Florida, if they learn all these techniques, it is profitable,” Jayachandran said.

Read more: A passion for agroecology

FIU on the forefront

Already involved with the local farm community, Bhat and Jayachandran, in collaboration with retired U.S. Army Col. John Mills, who now serves as president of non-profit Redland Ahead, debuted the Veterans and Small Farmers Outreach Program at FIU in early 2015. The initiative caters to former soldiers and new or aspiring minority farmers. Just as FIU’s College of Business runs a successful small business development center for budding entrepreneurs, Bhat and Jayachandran have established the equivalent for would-be farmers.

Funding comes from a source that understands the value of fostering new enterprise: the U.S. Department of

Agriculture’s (USDA’s) Office of Advocacy and Outreach. With the current staff of the USDA already busy serving traditional, established farmers, legislators appropriated funds to mobilize universities and nonprofits around the country to help new agricultural startups. In 2012, the USDA launched the Hispanic-Serving Agricultural Colleges and Universities (HSACU) program, which was approved in the 2008 farm bill. FIU was among the first universities in the nation to receive the designation.

The professors already had a history of securing grants from the USDA: Combined, they have brought in approximately $7 million over the years from the National Institute of Food and Agriculture to conduct research, train students and engage in community activities. So the two jumped at the opportunity given by the USDA to apply for nearly $170,000 in support of the local farming population. The grant has since been renewed for a second year.

At around the very same time that Garfield Jarrett was wondering where his life was headed, the professors were putting some of the recently awarded USDA money toward launching the Veterans and Small Farmers Outreach Program in the heart of South Florida farm country, the Redland Agriculture Area.

Facilitating financial help

Within the first nine months of launching, the program directly served more than 90 new farmers. Many wanted information about USDA microloans—up to $50,000 in support of startup enterprises—and FIU staff worked with them to complete the required application.

“We help them figure out what documents they need to bring in, how to fill it out, what kind of information they need,” says Nina De la Rosa, the farm education and outreach coordinator at FIU and an alumna of the university. “Every client takes about three to four hours.”

De la Rosa translates the application for her Spanish-speaking clients, which account for the vast majority of those who walk through the door, the greatest numbers hailing from Central America. Language barriers aside, the 8-10 page document simply scares off some people looking to break into the industry.

“It’s a little confusing,” agrees Nancy Mundo, the farm loan manager at the USDA’s local Farm Services Agency and one of the people who refers clients to De la Rosa. “Farmers usually want to be on their farms. If you give them the application, a lot of them may not come back because they don’t want to fill out that application because it’s too intimidating.”

The allure of financial help has achieved its goal of “trying to bring people into the farming industry,” Mundo said. But with the popularity of the microloan program has come even more work for an already overwhelmed agency.

“Without [FIU’s] help, we would be bombarded, and we are bombarded. That is just one area that has been alleviated: We don’t have to sit with the potential borrower and help him or her fill in the application. Nina helps them, and it takes a burden off us.”

In addition to assisting with the all-important paperwork, De la Rosa and a student assistant organize monthly workshops led by USDA officers, experts from FIU and others within the industry. These address technical skills such as beekeeping, composting and disease management. And meetings on business topics such as budgeting and marketing are offered, regularly bringing together as many as 20 participants at a time to take notes, share experiences and get to know one another.

First-rate field experiences

Also critically important, the program gives would-be farmers a chance to participate in “rotations” at several of the 16 local farms with which FIU has established partnerships.

Jarrett likens the opportunity to the practicum he completed for his social work master’s degree, which had him working under supervision at a VA hospital, a substance abuse treatment center and a nursing home. Here, aspiring farmers learn the ropes by serving paid apprenticeships in farm management at established operations that specialize in fruit and vegetable production, animal husbandry and nursery-plant production.

De la Rosa has seen firsthand how the experience of working under seasoned farmers changes participants’ outlooks, often moving them from simply a strong desire to work the land to something akin to determination. “Their business mindset is where we see the greatest shift,” she said. “It’s no longer ‘I’m going to do this because I love it.’ It’s ‘I’m going to do this because I love it, and I’m going to sit and plan how to make it profitable.’”

And she adds, “The main idea of the rotations is trying to create a new network of people that will be able to help these farmers. It would be great if you have one mentor, but it’s even better if you have four or maybe five.”

With his twin degrees from FIU in hand, Jarrett was among the first to enroll in the program and take advantage of all it offers.

“It opened my eyes to the resources that were out there,” he says, resources “that you wouldn’t know about unless you were in the industry or an established farmer.” Such knowledge helped Jarrett understand that he qualified for free soil testing of a property that he currently leases and on which he grows kale, Brussels sprouts, peppers and other crops. Another option open to him: up to $15,000 in help for irrigation work and pest management, the latter an especially important concern as he seeks to establish himself as an organic producer, one who chooses natural methods over herbicides and pesticides.

And getting to know the right people, as De la Rosa stressed, has boosted his chances of success. “As long as you’re willing to do the hard work, a lot of them are willing to help you,” Jarrett says of the more-experienced farmers and others he has met.

Agro-industry opportunities

Nestled between Biscayne National Park and Everglades National Park, southwest Miami-Dade County is the future for agroecology in the state, Jayachandran believes. Throughout Florida, more than 1.5 million people work in the state’s agriculture, natural resources and food processing industries, and that number is on the rise. In Miami-Dade County alone, agriculture has a nearly $2.7 billion annual economic impact, all the while occupying just 6 percent of the county’s available land, according to the South Dade Chamber of Commerce.

Bhat and Jayachandran believe this high-return industry represents untapped potential. By educating students and farmers about sustainable agriculture and farm business management, they are creating an ecosystem they hope will promote environmentally sustainable practices, positively impact food security and foster economic growth within the region. The two embrace education and innovation as the means to get there.

“Agriculture education is not just [about] a practice of farming. It is science and technology,” Jayachandran says. “It is exploring and discovering about biogeochemical processes, nutrient cycling, on-farm and off-farm pollution remediation measures, surface and groundwater management, bioenergy, food safety and security. If we are going to feed more than 9 billion people in the future, we have to get creative in how we use our soil resources and water resources.”

Achieving many of these goals requires research collaborations across FIU and with other higher education institutions. For example, agri-scientists and researchers in the International Center for Tropical Botany, a collaboration between FIU and the National Tropical Botanical Garden, work closely together to study and cultivate plants that could have new uses. The Agroecology Program is also working with the FIU Chaplin School of Hospitality and Tourism Management to develop farm-to-table food programs.

And a partnership with the University of Florida, the state’s land grant university, could lead to establishing an important facility in the heart of Miami’s agricultural community. While the idea is still in early consideration, the ultimate goal is to create a business incubator built around product development and food science. Such a facility in southwest Miami-Dade County would create jobs and promote entrepreneurial enterprises.

“The nation’s Hispanic-Serving Agricultural Colleges and Universities can accelerate research, and complement the extension and teaching of our land-grant universities,” said Arts & Sciences Dean Mike Heithaus. “At FIU alone, we are helping to develop more resilient crops, combat invasive pests, develop agribusiness opportunities and training the next generation of farmers. In many ways, the collaboration and complementary roles played by FIU and UF are a metaphor for what future collaboration with HSACUs should look like.”

Because Homestead and the Redland Agricultural Area are home to a wide variety of fruits, vegetables and ornamental plants, Jayachandran says it is a prime location for future research and economic development initiatives in agroecology. Already he and students have set up test plots to study plant biofuels and naturally occurring bacteria with the potential to serve as organic pesticides.

A blooming future

A lot of good could come out of the increased attention to South Florida’s agricultural landscape. Garfield Jarrett knows this on a personal level. Like Bhat and Jayachandran and others with a vested interest in the Miami-Dade farming community, he too has a vision.

More than just making a living, he hopes to combine his work on the land—in addition to crops, he also raises goats, sheep, chicken and ducks—with his social work background to change the lives of others. He looks forward to one day providing families with tours of his farm and inviting veterans and others to volunteer as a means to helping them heal, just as working the land has done for him. Through agriculture, he has found both a calling and a place where he truly feels at home.

“When I’m out there with nature,” he says, “it’s my way of coping, of doing something positive.”