|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Hispanolistic/E+ Collection/Getty Images

Gregory Fabiano, Florida International University

As another school year approaches, some caregivers, students and teachers may be feeling something new needs to happen to promote success in the classroom.

Daily report cards can be a great starting point.

As a clinical psychologist who studies how schools can help students with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, I know traditional report cards distributed three or four times per year don’t do enough to make a difference for children who are prone to outbursts or other challenging behaviors.

Studies conducted by my team and others support the idea that these students are better served by daily report cards.

Track daily progress

Daily report cards date back at least to the 1960s, when they were used in a study involving children attending a special education summer school.

Today they are commonly used for children with ADHD in both general education and special education classrooms. Daily report cards have also been used for students with autism without intellectual disability. And one study found that many teachers say they use versions of a daily report card for brief periods to address behaviors across many different school situations.

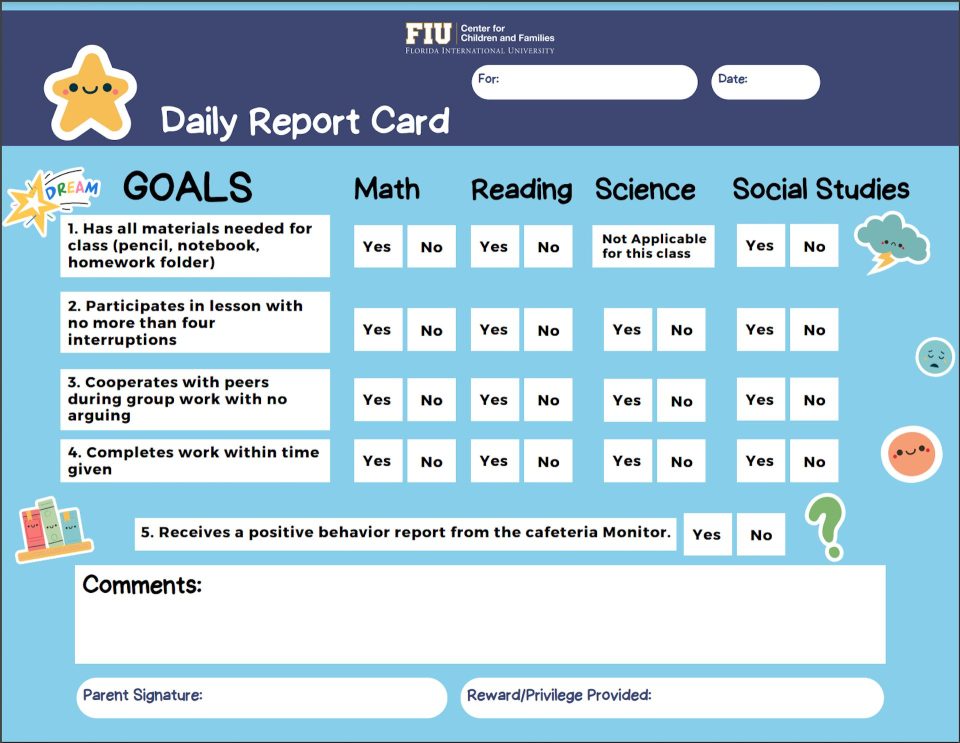

A daily report card can be very easy for teachers to create and use, either with an app or by developing them on their own. First, the teacher along with others – who may include the parents, principal, school psychologist or counselor, and even the child if appropriate – should meet to establish goals. Goals should be positively phrased, such as: “Completed work within time given” or “Participated in class discussions without interruption.”

Once set up, the daily report card can take just 10 seconds to complete. The time savings are significant when one considers the alternatives typically used in schools, such as repeated redirection or reprimanding, or sending the student to the principal’s office to be monitored.

Daily report cards also work.

A 2010 study evaluated children with ADHD where half had a daily report card and half did not. Those with the daily report card had an average of 4.5 fewer rule violations per 30-minute class than those without one. Extrapolating across a school day, that is 54 fewer daily rule violations on average, and over 10,000 per school year.

Florida International University Center for Children and Families, Author provided

Realistic goals

For many children with challenging behaviors, it is important to set goals that can be easily reached – at least at first.

Over time, the goals can be made more challenging as the child experiences success – a process called shaping. For example, if a child interrupts a lesson by calling out about five times per class, the initial goal may be set at “Participates in lesson with no more than four interruptions.”

This would represent an improvement, and it would also ensure the goal was reachable. Once the child met the goal for three to five days in a row, the goal could be changed to “Participates in lesson with no more than three interruptions.”

Positive parent-teacher communications

Teachers tend to communicate with caregivers more frequently when a child is experiencing difficulties in the classroom. But these communications often focus on negative behaviors. As a result, they can strain relationships between the caregiver and the teacher. Other times, it may result in the caregiver’s avoiding communication with the school.

Daily report cards can result in more positive and solution-focused communication instead of reports focusing only on what went wrong and can therefore enhance caregiver-teacher communication.

Motivating rewards

Importantly, the daily report card should be linked to home-based privileges and rewards so that children are motivated to meet daily goals.

At the end of the day, the child brings their daily report card home and, based on their behavior at school that day, home privileges such as an allotment of screen time or a slightly later bedtime can be used as rewards.

Importantly, this is not a punishment program in which a child loses privileges if goals are not met. It also is not bribing the child by providing a reward before an appropriate behavior is completed. Rather, the child starts the day without home privileges and earns them based on positive school behavior. The daily report card tells the child exactly what goals need to be met to earn the motivating privileges. This small difference can be quite powerful for the child because it puts them in charge of how they earn access to things they like to do at home based on how they behaved at school that day.

Evidence suggests this home-based reward system is one of the biggest factors in whether the daily report card is successful. It also provides a new opportunity for the child and caregiver to have a positive discussion about school each day.

Better than medication?

There is also evidence that the daily report card is a cost-effective approach for children with ADHD as an alternative to medication treatment.

My colleagues and I conducted a study in which children with ADHD were randomly assigned to start the school year with either medication or a daily report card. The parents of those assigned the daily report cards took part in classes that taught them how to provide home rewards for it. At the end of the year, the students who started with the daily report card had half as many discipline referrals and 33% fewer disruptive behaviors observed in the classroom than the students receiving medication. The daily report card approach also cost less than daily medication. The students who started the school year with the daily report card had overall treatment costs of US$708 less than the students starting with medication.

Teachers and caregivers who want to learn more about daily reports cards can check out the downloadable workbook or free app designed by my colleagues at Florida International University’s Center for Children and Families. Both resources allow caregivers and teachers to set goals and track a student’s progress. Starting the school year with a daily report card should help the child achieve the positive days needed to get a good grade on their report card at the end of the grading period.![]()

Gregory Fabiano, Professor of Psychology, Florida International University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.