By Eric Barton

When Kevin Evers killed three men in Miami Beach in 2003 simply because they wouldn’t turn down their music, it was by all accounts a cold-blooded act, and prosecutors sought the death penalty.

Then one of Evers’ attorneys, Stephen K. Harper, an assistant public defender at the time, found out a lot more about Evers. Unemployed at the time of the murders, Evers had lost his wife in childbirth. He had given up his daughter for adoption. His family had a history of serious mental illness. Nothing could excuse what Evers had done, but Harper hoped the personal information might save his client from death row.

Harper prepared what’s known as a mitigation package, a legal document that lists reasons and evidence in support of sparing a defendant from lethal injection. “If you prepare the mitigation evidence effectively, you’ll often convince prosecutors to waive death or to offer a plea to something less than death or to get a jury to vote for life [imprisonment],” Harper said.

But while this mitigation evidence can often save defendants from death row, its collection is rarely done right in Florida capital cases. That’s what Harper has found as co-director of Florida Center for Capital Representation at the FIU College of Law. It is the only organization in Florida that consults with, teaches and assists lawyers in all aspects of capital representation. Those efforts are made possible through a two-year $620,000 grant from the Themis Fund, an anti-death penalty group.

Among other activity at the center, Harper helps attorneys throughout the state prepare mitigation evidence through his “death penalty clinic.” He teaches a course on the subject to law students and each semester selects several of them, for which they receive course credit, to work with lawyers engaged in capital cases. The clinic has closed 34 cases and is currently consulting on 83 cases.

Among other activity at the center, Harper helps attorneys throughout the state prepare mitigation evidence through his “death penalty clinic.” He teaches a course on the subject to law students and each semester selects several of them, for which they receive course credit, to work with lawyers engaged in capital cases. The clinic has closed 34 cases and is currently consulting on 83 cases.

In addition to the center’s work on mitigation, Harper and co-director Karen Gottlieb worked with others to encourage the legislature to change Florida’s death penalty law. And while the legislature did change the law, requiring a life sentence unless the jury voted for death by a vote of 10-2 or more, it did not go far enough, as Harper and Gottlieb had predicted. The state’s Supreme Court declared the law invalid in a ruling in October, deciding that juries ought to be unanimous when sentencing a defendant to death.

Rewriting the state’s flawed law is crucial to attorneys who handle death penalty cases, said Edith Georgi, a Miami-Dade County assistant public defender who tried more than 75 jury trials from 1981 until her retirement in November. Georgi said Harper’s work has been instrumental in bringing about a change. “He really knows how to pull people together,” Georgi said. “Steve’s organization has been extremely effective in getting results. It’s saving lives, definitely.”

Among Harper’s first tasks was simply to begin compiling all the pending and possible death penalty cases in Florida. No state agency keeps track of pending capital cases, so a clearinghouse was created, based on data from the 20 judicial circuits, to show trends.

The data will also determine which Florida circuit courts seek the death penalty most often and which state attorney offices are most effective at getting death penalty convictions. Initial results have shown that the now former prosecutor in Jacksonville sought and received death penalty convictions far more than any other circuit in Florida, Harper said.

One of the many reason for this is that trials are not conducted uniformly throughout the state. For example, jury selection in capital cases takes only a day or two in Jacksonville, while attorneys in Miami-Dade will often spend more than a month on the same task, Harper said.

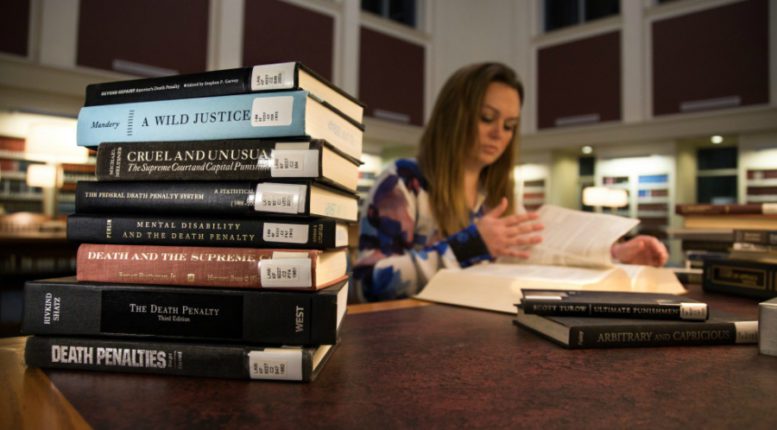

To help educate defense attorneys on how to hold more effective jury selection, Harper enlisted third-year law student Ashley Allison, pictured above. She is working on a comprehensive memo that will outline how to effectively pick juries and make sure the trial record is clear if denied opportunities to question jurors. It will offer suggestions on how to question potential jurors, asking about their potential biases regarding the death penalty and any personal history that might influence how they would vote if they make the jury. Once completed, the memo will be circulated to Florida lawyers who work on death penalty cases.

“There’s huge variations in how death penalty cases are handled in Florida, and it shouldn’t be that way,” Allison said. “We’re hoping to create some uniformity in the way death penalty cases are defended.”

Allison became interested in the subject based in part on her own family history. Allison said her great-great-grandfather died in jail, after waiting 15 years for a trial. “I grew up realizing the justice system doesn’t always work,” Allison said. She interned at the Miami-Dade Public Defender’s office and will start work there full time after graduation.

In working with attorneys to more effectively prepare mitigation packages, Harper encourages them to hire mitigation specialists who can help gather evidence.

Among them is Deb Alberto, of Able Detectives in Melbourne. A former investigative journalist, Alberto now spends her days combing documents and interviewing family, friends and former co-workers of defendants who face the death penalty.

“It’s a life history investigation,” Alberto said. “The prosecution often makes the person look one-dimensional and defined by the worst thing they’ve done in their life. We try to look at the whole person as a way to possibly bring some empathy.”

Alberto helped prepare mitigation evidence in the case of Jessica McCarty, the Palm Bay mother who murdered her three children in 2015. The mitigation package showed that McCarty had a history of mental illness that went untreated. The evidence was enough to convince prosecutors to drop the death penalty and agree to a plea deal that sent McCarty away for life.

McCarty’s case is evidence of the importance of what Harper’s clinic is doing, Alberto said. “It’s good to see that there’s a center making sure that justice is done right,” Alberto said.

In the Evers case, Harper and his co-counsel presented mitigation evidence that showed their client suffered a bipolar disorder, psychotic episodes and brain damage that kept him from controlling his impulses. Evers had pleaded guilty, leaving the fate of his sentencing to a judge, and the judge agreed to spare Evers from the death penalty. Evers is now serving a life sentence in a Martin County prison.

“Once we gathered that mitigation package, we had a pretty convincing argument to present to the prosecution and ultimately to the court,” Harper recalled.

Now, Harper and his colleagues at the death penalty clinic hope they can teach other attorneys how to do the same. ♦