Many of the Hongkew refugee children were born in China. Some attended schools that were organized by educators in the refugee camps. All of these children spoke German and English, a few had learned Chinese. Photo by Arthur Rothstein

The Jewish Museum of Florida-FIU presents the U.S. premiere of Stranded in Shanghai: Arthur Rothstein’s Photographs of the Hongkew Ghetto, 1946, the timely exhibition featuring a lesson from history about tolerance, compassion for human suffering and solidarity. These themes ring true just as powerfully today during our troubled times as they did in the 1940s, when Shanghai became the last hope for desperate refugees fleeing Nazi terror.

There were 20,000 European Jews who escaped certain death by spending the war years in Japanese-occupied Shanghai, with nowhere else to go because they were turned away by so many other countries. Many of these refugees fled their homes in Europe under great duress without transit papers or money, and didn’t know what happened to loved ones left behind. Just like so many refugees and migrants facing similar issues today, they had no other place to escape to and surely would have died if not for this sanctuary in Shanghai.

The photographs in this exhibition are the only remaining visual testimony of this refugee crisis. The exhibition is on view March 13 – May 20 at the Jewish Museum of Florida-FIU, located in the heart of Miami Beach’s Art Deco District at 301 Washington Avenue.

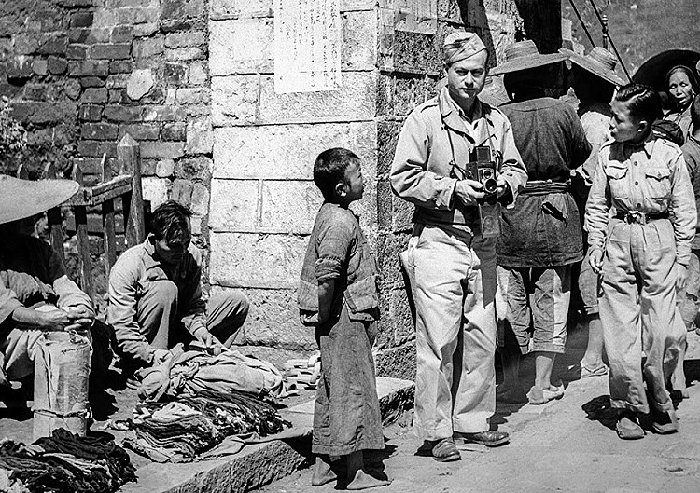

After the end of World War II Arthur Rothstein became the chief photographer in China for the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA). While working for UNRRA he photographed the community of European Jewish refugees in Shanghai during April of 1946. By this time Rothstein had more than ten years of intensive experience working as a social documentary photographer for the U.S. Farm Security Administration, the US Office of War Information, and Look Magazine.

“The Jewish Museum of Florida-FIU is thrilled to present the U.S. premiere of Stranded in Shanghai,” said the museum’s Executive Director, Susan Gladstone. “We are honored to shine a light on this little-known segment of history that mirrors so much of our present. We must know history in order to proceed successfully with our future.”

“Rothstein’s works are truthful and unflinching, and were it not for these photographs the experiences of these refugees and the lessons we can learn from them today would have been lost forever,” adds Gladstone. Miami Beach is the first city in the U.S. to present this exhibition, after showings in Prague and at Slovenia’s Festival of Tolerance.

Hongkew, Shanghai, China. April 1946

Jammed into communal housing, German and Austrian refugees

live out of steamer trunks and sleep in bunkbeds.

Clothing is hung from the ceiling to save space. Photo by Arthur Rothstein

ECHOES FROM THE PAST RING TRUE TODAY

Throughout his career, Rothstein considered himself to be a photojournalist and a “social documentary photographer,” capturing images that explored issues of class, poverty, discrimination and economic opportunity. The photographer’s life, and his 50-year career as one of America’s most prominent photojournalists, offer multiple lessons to our present generations regarding displacement, migration, resettlement and tolerance.

Rothstein’s photographs provide a window into the collective experience of the refugee community, and into the lives of individuals who had found a temporary home ̶ and tolerance ̶ in Shanghai. After the war ended, these stateless refugees became “displaced persons.”

Most would survive the War, despite the severe conditions and deprivations of life in the Japanese-occupied port city. At war’s end in 1945 many were destitute and unable to return to Europe, facing an unwelcoming world where once again most countries would not welcome Jews. Even more terror was imminent: these 20,000 refugees would soon be forced to flee again due to the encroaching Civil War in China. Rothstein, one of the world’s foremost photojournalists, hoped his photographs would bring attention to their plight.

In the spring of 1946, Rothstein, the young Jewish-American documentary photographer, was discharged from the American Army in China and was hired as chief photographer for the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA). The UNRRA was an international relief agency founded during World War II to give aid to areas liberated from the Axis powers. Rothstein’s mission was to create a photographic record of UNRRA’s enormous humanitarian effort (spending over $518 million dollars) to defeat hunger and rebuild infrastructure in China. UNRRA also assisted “displaced persons.”

A special preview reception is free for Members of the museum, FIU faculty/staff and students on Monday, March 12 from 6:30-9:00 p.m. ($10 for non-members). At the opening, the photographer’s daughter, Ann Rothstein-Segan, PhD, will present a lecture and intimate portrait of her father’s life and his illustrious career. She will describe the unusual circumstances that brought her father into this remote enclave of European Jews in China and reveal how his photographs of the community were lost for twenty-five years, only to be recovered with the help of an unlikely collaborator.

On Sunday, March 18, at 5:00 p.m. the museum will present a film screening of Above the Drowning Sea, the film about these European Jews escaping the Nazis to Shanghai. Filmed in six countries and over seven continents, the film explores via personal interviews the intense experiences and life-long bonds shared between Jewish refugees and the Chinese residents of Shanghai, whose tolerance and support were critical in their survival.

MORE ABOUT “STRANDED IN SHANGHAI”

Rothstein’s photographs provide insight into the historical role of the photographer in the service of international organizations, and into the important role of photojournalism in zones of conflict and humanitarian conflict.

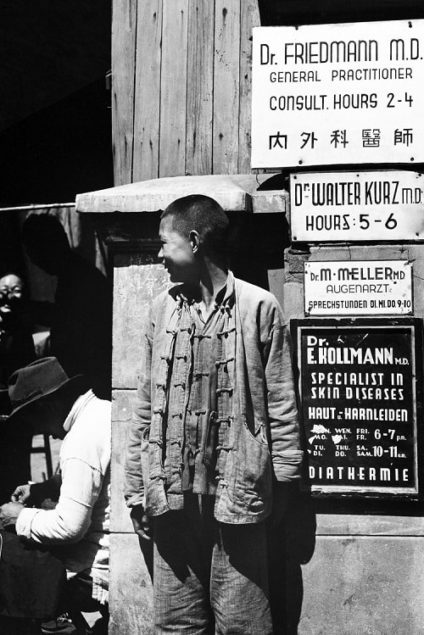

This exhibition tells the stories and experiences of the refugees of the still mostly unknown Shanghai Ghetto – Jewish refugees from Austria, Germany, Poland, Czechoslovakia and Hungary who sought sanctuary in Shanghai at a time when, with rare exceptions, the entire world was refusing to accept Jews.

Rothstein’s photographs include striking images: the haunting entrance gate to the ghetto, the crowded conditions of communal homes, a glimpse of what it was like to live in meager and unsanitary conditions with food and clothing rations as a lifeline, the lives of children and infants who were born into these conditions, the harsh severance of communication with Europe, and the challenge of searching for those left behind.

Many European Jewish refugees arrived in Shanghai from late 1938 through 1940, due to the state-sanctioned violence that resulted in Kristallnacht (Crystal Night or Night of Broken Glass), a pogrom against Jews in Nazi Germany on November 9-10, 1938. Jews were systematically disposed of money and property and fled to Shanghai with few resources.

In 1946, the UNRAA proposed to repatriate 1,700 Germans and 1,300 Austrians to their homelands, but only a few returned. Most refugees went on to find permanent homes in Israel, the U.S., Australia and other countries.

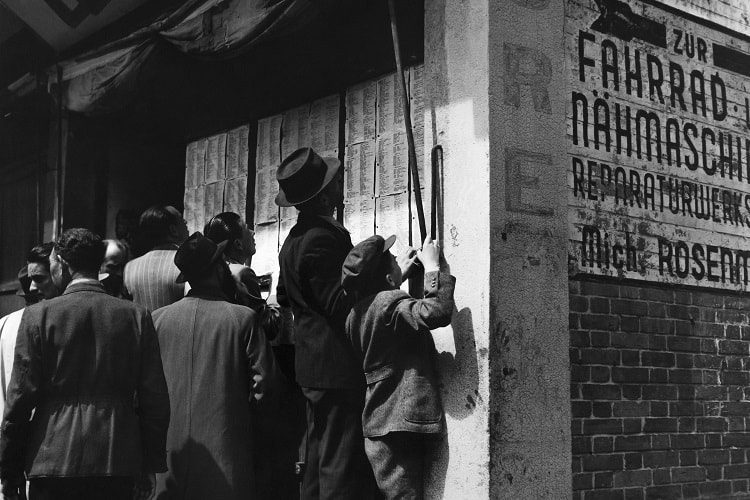

Hongkew refugees glumly read the Shanghai government proclamation ordering them to evacuate their homes. Even after the war ended refugees were engaged in the daily struggle to maintain a minimum dignified existence. This eviction notice was posted unexpectedly, directing residents to move during Passover. Relief officials from UNRRA later secured a cancellation of the order.

ABOUT THE ARTIST

Arthur Rothstein (1915-1985) was one of America’s premier photojournalists of the twentieth century. During his 50-year career, he created an indelible visual record of life and opened windows to the world for the American people during the golden era of magazine photography. He grew up in New York City, and as a student at Columbia University he founded the University Camera Club.

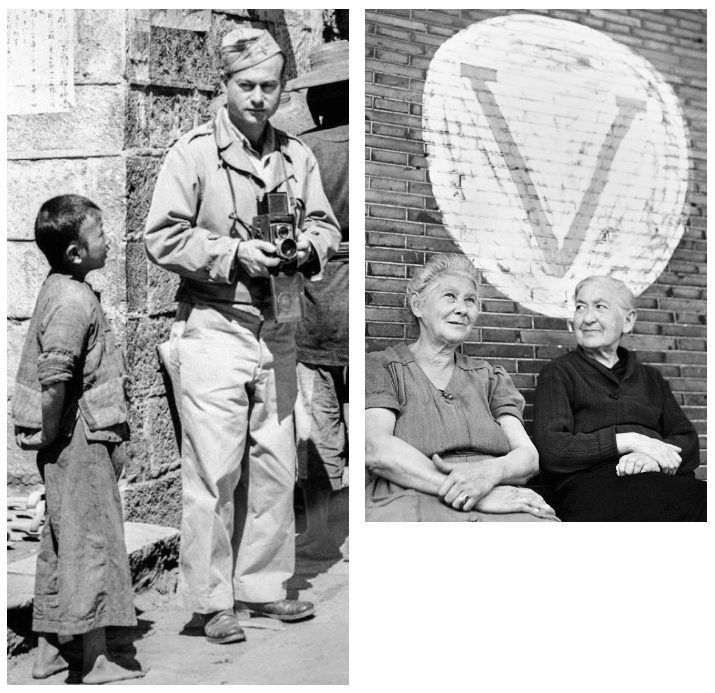

Two Refugees and “V“ Sign, Hongkew, Shanghai, China (April 1946) Photo by Arthur Rothstein Ernestine Brandt, age 74 and Emma Scharff, age 70. Two German ladies, relieved by the allied victory over the Japanese, but uncertain of their future. They are relaxing in the courtyard of the Ward Road heim for European Jewish refugees where they have been living since 1940. (“V for Victory” had been an important symbol of the allied campaign during the war.)

He was hired early on as one of the first photographers to document and publicize the widespread displacement and migration of farmers and industrial workers, caused by the Great Depression. From 1935 through 1940, Rothstein and the other photographers working for the Farm Security Administration (FSA) Photo Unit shot some of the most significant photographs ever taken of rural and small-town America. One of Rothstein’s most well-known photographs is the iconic image of the Dust Bowl era, A Farmer and his Two Sons during a Dust Storm in Cimarron County, often included in high school history text books to illustrate the era.

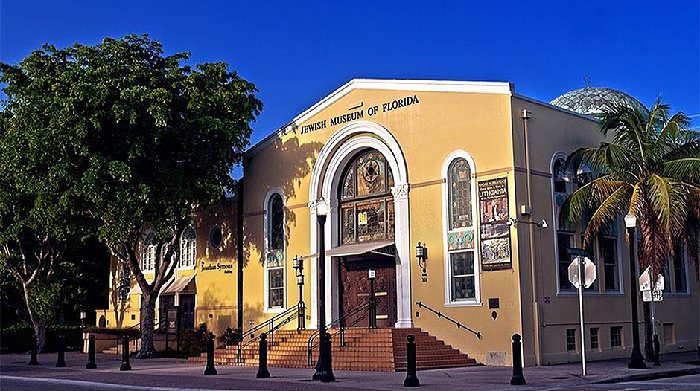

ABOUT THE JEWISH MUSEUM OF FLORIDA-FIU

The Jewish Museum of Florida-FIU serves as a major cultural attraction and source of information for a wide audience of residents, tourists, students and scholars of all ages and backgrounds from throughout the state, nation, and the world. Located in a former synagogue that housed Miami Beach’s first Jewish congregation, the museum’s restored 1936 Art Deco building and 1929 original synagogue are both on the National Register of Historic Places.

The 301 building features nearly 80 stained glass windows, a copper dome, marble bimah and many Art Deco features including chandeliers and sconces. The Jewish Museum of Florida is accredited by the American Alliance of Museums. The museum is open Tuesday-Sunday from 10 a.m.-5 p.m. Closed on Mondays and holidays. Admission: Adults $6; Seniors $5; Families $12; Members and children under 6 always free; Saturdays-Free. For more information call 305-672-5044 or visit www.jmof.fiu.edu. The Museum is supported by individual contributions, foundations, memberships and grants from the State of Florida, Department of State, Division of Cultural Affairs and the Florida Council on Arts and Culture, the Greater Miami Jewish Federation, the Miami-Dade County Tourist Development Council, the Miami-Dade County Department of Cultural Affairs and the Cultural Affairs Council, the Miami-Dade County Mayor and Board of County Commissioners and the City of Miami Beach, Cultural Affairs Program, Cultural Arts Council, and the Funding Arts Network.

Comments are closed.