The cheerful acknowledgement we hear at the end of the classic film It’s A Wonderful Life was spoken by James Stewart. The movie tells the story of a man who loses faith in life and wants to kill himself but is prevented from doing so by a guardian angel named Clarence.

It’s A Wonderful Life is quintessential Americana, depicting small town life full of optimism and confidence. But when it opened in theatres in 1946—barely a year after the end of World War II—the rosy themes seemed at variance with a vastly changed world.

It would take another 20 years before the film caught on with mass audiences via television.

The famous Frank Capra-Stewart film played again recently on the USA Cable channel. It was probably the 15th time I have viewed this movie; the production is so good and so uplifting you will shed a tear, I promise you.

It was along about the time the film debuted that we stopped calling Mr. Stewart “Jimmy,” settling on the more mature “James.”

He had been in movies since 1935—three years after graduating from Princeton with a degree in architecture—won a Best Picture Oscar for The Philadelphia Story (1940) and served in World War as a flying officer after volunteering at age 33. When he returned from the war after flying more than 20 combat missions, Stewart wanted to be his own boss in films and within a few years became the first major star to agree to a percentage of a movie’s profits instead of a guaranteed salary.

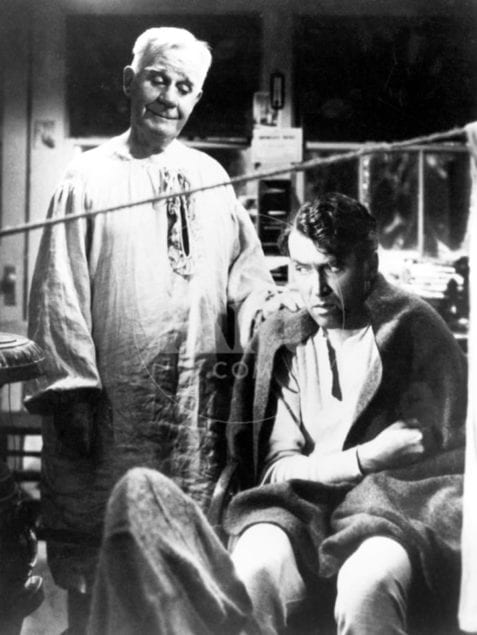

Film critics were not kind to Stewart in those days. His drawl and hesitant speech pattern were fair game for them. He insisted on more serious parts and proved he could handle them. One of his first “against type” films was Call Northside 777 (1948), where he played a crusading newspaper reporter who saves an innocent man. Always a prolific actor, he followed that film with four Alfred Hitchcock productions, including the classics Rear Window (1954) and Vertigo (1958) and a series of westerns that were critically acclaimed and box office hits. Two later Stewart films considered outstanding were Anatomy of a Murder (1959) and Flight of the Phoenix (1966). These films carried harder, more complex roles which changed his screen image.

Despite his status as a first-rank star and distinguished military background (he retired as a Brigadier General in the U.S. Air Force), Mr. Stewart usually kept in the background when it came to politics. But by 1972 he was in the spotlight when the Republican Party held their national convention at the Miami Beach Convention Center.

A lifelong Republican, he made the introductory speech for First Lady Pat Nixon. As the lanky Stewart made his way to the podium, the orchestra struck up a rousing rendition of the song Ragtime Cowboy Joe, which—more or less—served as the unofficial theme song for this national icon. The lyrics couldn’t be more apt…

He’s a hifalutin’ scootin’ shootin’

Son-of-a-gun from Arizona

Ragtime Cowboy Joe

Bob Goldstein is a retired broadcaster who has lived in South Florida for more than forty years. He is a veteran political activist (dsdcfl.org) and a member of the South Florida Writers Association. If you’d like to comment on Bob’s columns, send your response by email to robertgrimm62@yahoo.com.