My heart skipped a bit when I read the headlines on the morning of January 4 and learned that the Department of Interior planned to open up more than 90 percent of our waters to offshore drilling, including those off the coasts of Miami, Broward and the Florida Keys.

I set the newspaper down and closed my eyes. I was instantaneously transported to my favorite beach in Miami: Bill Baggs Cape Florida State Park, which occupies the southern tip of Key Biscayne. My wife and my boys and I will go out there to swim, sunbathe on the wide beaches, rent bikes, or just walk the nature trails. Every now and then we’ll tour the Cape Florida Lighthouse, the oldest building in South Florida, and explore the native wildlife planted in the aftermath of Hurricane Andrew.

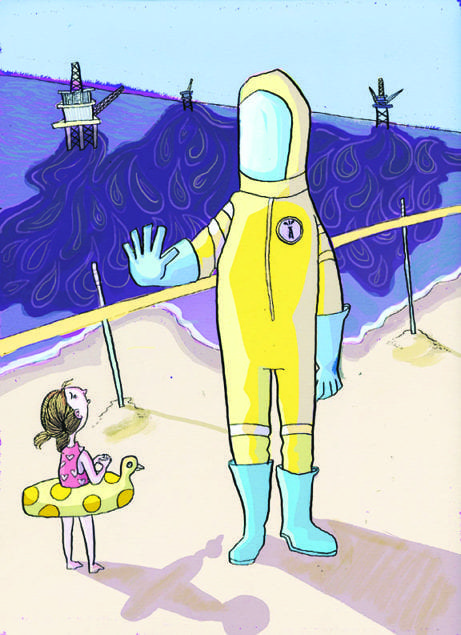

The trouble is that historic parks like Bill Baggs—like many parks on and around our shorelines—would likely not survive the devastating effects of an oil spill.

The Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico was the largest marine oil spill in the history of the petroleum industry, and its impacts on the environment, wildlife, human lives, and the economy were catastrophic. Eleven workers died from the explosion. Hundreds of cleanup workers and Gulf residents were exposed to toxic chemicals. Thousands of birds, dolphins, sea turtles, and other marine animals were killed. Endless miles of shoreline were affected.

Oil-drenched seabirds and suffocating marine mammals are emblematic images of catastrophic oil spills; in fact, an oil-soaked pelican made the cover of TIME Magazine after the Deepwater Horizon spill. However, oil is extremely toxic to all wildlife, from microscopic plankton to 30-ton whales. The oil and dispersant mixture permeates the food chain through plankton, impacting marine creatures at multiple levels.

What happens below the surface after an oil spill? Herbivorous wildlife (such as sea turtles) consumes vegetation coated with oil particles. Fish and other carnivorous wildlife feed on zooplankton contaminated by floating oil. Shorebirds consume prey organisms that have been exposed to oil sediments washed onto the shoreline. Baleen whales are unable to eat as the oil clogs their filtering systems, and top predators become vulnerable to large quantities of pollutants through bioaccumulation.

But this is only in the immediate aftermath. You see, oil persists in the environment long after a spill. On sandy beaches, the oil sinks deep into the sediments. In tidal flats and salt marshes, it seeps into the muddy bottoms. Florida residents should keep these visuals in mind, seeing as how beach tourism on the Atlantic and Gulf coasts generates nearly fifty billion dollars and half a million jobs annually.

The decline in seafood catches, as well as the deformities and lesions observed in shrimp, fish, and dolphins, indicate that the Gulf ecosystem is still in crisis eight years after the Deepwater Horizon catastrophe. Six large oil spills have occurred in the Gulf of Mexico in recent times—spills that continue to imperil the Gulf’s rich abundance of wildlife and its threatened and endangered species. It’s an important lesson for the Atlantic coast of Florida, for South Florida citizens, and for the Department of the Interior: No matter how much oil or gas may be mined from it, “drilling is killing.”

Author’s Bio

Leopoldo Llinas is a forward-thinking father who hopes to educate the young men and woman who will make this world better. He holds a PhD in Marine Biology and Fisheries from the University of Miami Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science. leollinas@gmail.com