It’s a cold, February afternoon – cold by South Florida standards, anyway – and my boys are walking the picturesque boat basin at Deering Estate, counting blimp-like shapes protruding from the water. As sunset looms, the blissful silence is broken by an explosive exhalation in the water as a pair of round nostrils rise to the surface. By now, the boys have lost count, in part because it’s impossible to tell one manatee’s nostrils from another’s.

Manatees often occupy this warm water basin to escape the colder waters of Biscayne Bay. To keep from excessively losing body heat, manatees generally avoid such conditions and find refuge instead in tropical and subtropical waters. When the Florida temperatures dip in the winter months, they migrate further south and seek out natural springs or areas where power plants discharge warm waters.

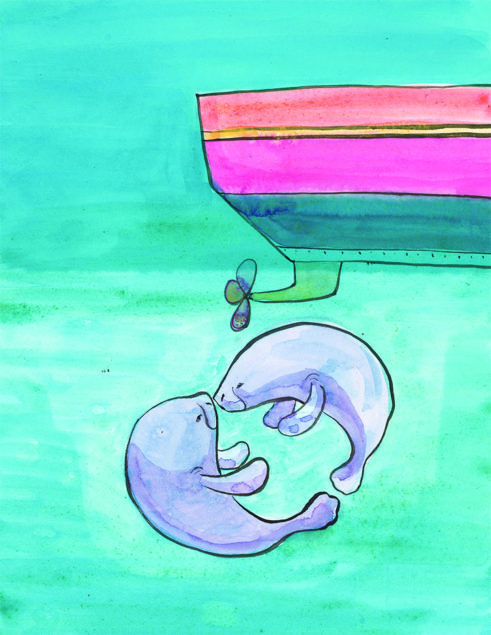

To Floridians, the charismatic sea-cows’ features are unmistakable: a bewhiskered face, depressed eyes, paddle-like flippers, and an attempt at a smile. As Florida’s official marine mammal, the manatee is prominent in our art and folklore. An enduring myth about these slow-moving creatures is that they inspired the alluring Sirens described in Homer’s Odyssey. I suppose a manatee with seaweed draped over its head could somehow be mistaken for an unsightly mermaid… or perhaps the sailors had been at sea too long. Whether the myth holds true or not, manatees’ resemblance to mermaids is, well, largely exaggerated.

As strict herbivores, manatees live in coastal environments where aquatic plants are plentiful. When their teeth wear down and fall out due to the abrasive plants that make up their diet, manatees simply reproduce new molars at the back corners of their mouths; the new teeth migrate forward, as if on a conveyor belt, for their entire lives. My older son loves this adaptation: “How much money do they have from the tooth fairy?!” he asks every time.

Being mammals, manatees must surface every few minutes to breathe, and each instance puts them at risk of collisions with watercrafts. Their bodies bear the scars of their sometimes grave encounters with speedboats; these days, scientists can identify individual creatures by their scars or mutilated flukes.

In 1973, the Florida manatee became protected under the U.S. Endangered Species Act. At the time, there were several hundred left in existence. In 2017, more than four decades later, there were at least 6,000 manatees in the state, and the species was reclassified from “Endangered” to “Threatened.”

Floridians deserve a great deal of credit for adjusting their behaviors to allow the state’s manatee population to rebound. However, as South Florida’s population continues to grow, and with the threat of significant algal blooms and declining seagrasses, the manatee’s survival is far from assured. We must embrace our role as stewards of these mythical, compassionate creatures — and sound the siren to ensure that they are able to flourish in Florida’s waters for decades to come.

Leopoldo Llinas is a forward-thinking father who hopes to educate the young men and woman who will make this world better. He holds a PhD in Marine Biology and Fisheries from the University of Miami Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science. leollinas@gmail.com