I had this captivating biology teacher—a real firecracker who could go on and on about exotic animals and plants from all over the world.

His enthusiasm was contagious. However, the information he delivered (exciting as it was) was never significant to me as a student sitting in his classroom. For that reason, I always felt like something was missing.

Twenty years later, I’m the one at the front of the classroom, driven by the philosophy that students learn best through personal experiences that are physical, emotional, intellectual and spiritual. I am fortunate enough to teach at an institution where “learning by doing” has replaced “learning by repetition.” With the support of Palmer Trinity School, I frequently take my students out of the classroom and into the natural world, whether it’s their own backyard in Biscayne Bay or the mountains of Patagonia. Of all these escapades, the one that impacts every student, without fail, is a shark research expedition off the coast of Miami.

The day starts early with a check-in at the marina prior to boarding a boat. We leave the dock and motor out to our fishing site while some adventurous scientists—our guides from the Shark Research & Conservation Program (SRC) at the University of Miami (UM)—provide a brief overview of what they do, how they do it, and why it all matters. My students have been signed up as UM volunteer “Citizen Scientists” for the day to help the SRC team conduct research that aids in the conservation of sharks. This is important given widespread declines in many shark populations, including in South Florida due to over fishing. SRC projects that our students are involved with range from understanding the ecological importance of sharks to the effects of climate change on sharks.

Arriving at our destination (somewhere in the middle of the ocean), the students help deploy drum lines in strategic locations around the study site. A drum line is a stationary fishing unit comprised of a baited circle hook, which allows hooked sharks to swim freely in large circles, passing water through their gills and thereby reducing stress and promoting shark vitality. These drum lines bob and soak in the ocean for at least an hour.

While we wait, the scientists discuss the duties to be performed once a shark is caught and the various species found in these waters. You can see the students’ minds churning: What will we catch today?! A hammerhead shark, a nurse shark, a tiger shark…?

After the hour is up, we retrieve the drum lines. If the line comes up empty, the crew re-baits the line, and we deploy it a second time. When there is a shark on the line, the excitement is palpable. The students stand there, mouths agape, as the magnificent creature is carefully secured to lifted out of the water and stationed on a partially submerged platform at the rear of the boat, where a water pump is placed in its mouth to that allows the flowing seawater to pass over the sharks gills, thus allowing them to breathe and stay in good condition during the quick scientific work-up assist with breathing.

All research tasks are designed with shark welfare and scientist safety in mind. Under the guidance of the SRC, the students become citizen scientists. First task: Test the shark’s reflexes nictitating membrane, or translucent eyelid, in order to determine the shark’s stress level. This is done by checking the response of their nictitating membrane or translucent protective eye covering, that sharks will raise to cover their eye when they feel pressure on their eye or face—a reflex that helps protect their eyes from potential injury from a prey. Using a syringe filled with seawater, a student blasts squirts a few ml of water towards the shark’s eye, waiting to see if the membrane raises or “fires off.” If it does, then the shark is in good shape. If it doesn’t, it means the team must work fast, as the shark is a bit stressed.

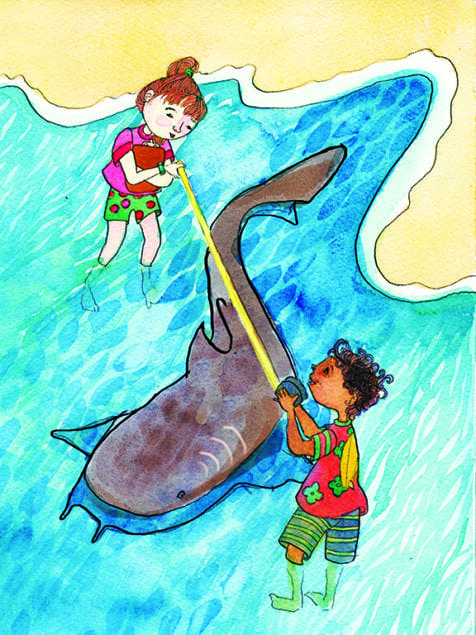

After taking standard measurements of the shark, the students will tag the shark for identification and tracking purposes. One student inserts the tag into at the base of the shark’s dorsal fin rays while another records the tag number. They will then take a small tissue sample from the dorsal fin for genetic tests, dietary and ecotoxicology analysis, i.e. to study the effects of chemicals on aquatic organisms.

The students look on as the SRC experts complete several other tests, including a blood draw and occasionally an ultrasound for pregnant female sharks. The scientists must record information for each individual caught, including the shark’s sex, sexual maturity state, and species.

Final task: Test the shark’s nictitating membrane reflex once again before saying our goodbyes and releasing it back into the water.

Not only are students obtaining hands-on research experience, but they data they gather will be helpful to policy makers to make effective shark conservation strategies.

As we head back toward the marina, the students gaze at the horizon, anxious to tell their friends and parents and siblings about their interactions with these magnificent apex predators. In the end, this rewarding, empowering and incredibly personal experience is not only educational—it will inspire them to learn more and do more. And that’s truly significant.

To learn more about SRC, visit www.SharkTagging.com.

Author’s Bio

Leopoldo Llinas is a forward-thinking father who hopes to educate the young men and woman who will make this world a better place. He holds a PhD in Marine Biology and Fisheries from the University of Miami Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science. leollinas@gmail.com

Shark tagging is cruel and should be banned asap. Its slowly destroys their main steering fin with toxicity and scares away their primary food source leaving them with us Humans that cannot hear that GPS signal.