|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

The novel coronavirus poses a unique predicament for the homeless. If a homeless person contracts COVID-19 and needs isolation, where do they go? They can’t go to a shelter. The virus can spread like wildfire in such communal settings. Even if they find a place to quarantine, who will monitor their health?

The Herbert Wertheim College of Medicine (HWCOM) joined forces with the Miami-Dade Homeless Trust and the Rotary Club of Miami for a telehealth initiative to help homeless individuals infected with the virus.

“Because people with COVID-19 can decompensate quickly, and the homeless are a particularly vulnerable population that lacks resources, we wanted to make sure that these patients are followed closely,” said Dr. Gregory Schneider, associate professor in the Division of Family and Community Medicine.

The first cases of COVID-19 in the South Florida homeless population were discovered in April. A

26-year-old homeless man was the first to die from the virus. The Trust started isolating infected individuals in hotel rooms and providing them with meals and cell phones.

One of those individuals was Romel Aristide, a 51-year-old insulin-dependent diabetic, homeless, jobless. Alone in his hotel room, he longed for his wife and children in Haiti and worried he could not work to provide for them. He was sick, and he was sad until he started getting calls from two total strangers.

“Skylar and Sabrina called me twice a day. They tell me God has not forgotten you. They got me insulin. They give me strength,” Aristide said of FIU medical students Skylar Korek and Sabrina Gill. “I feel alive when they call.”

When the virus broke out, medical students wanted to do something to help the homeless but weren’t sure what they could do.

“Dr. Schneider suggested we contact the Homeless Trust, and that’s how it began,” said Kyle Sellers, a third-year medical student.

“One of the biggest challenges the Trust faced when COVID-19 hit was to provide symptom monitoring, wellness checks, referrals for medical care and medical clearance for persons experiencing homelessness in quarantine or isolation,” said Ronald L. Book, chair of the Miami-Dade County Homeless Trust. “FIU’s College of Medicine stepped up to offer telehealth services to this vulnerable population.”

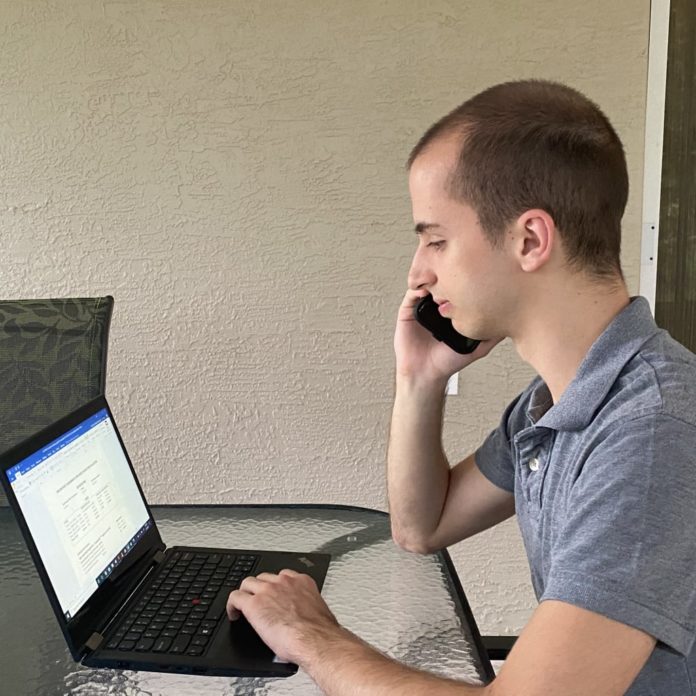

With Schneider’s guidance, students put together a team of HWCOM volunteers. More than 40 medical students and six faculty members signed up to help. Their job, to call people in isolation daily to check up on their health. The students work in pairs with a faculty supervisor. So far, they have monitored 27 individuals.

“We ask them a list of questions to calculate a person’s risk of having more significant complications of COVID-19,” said Schneider. Those at higher risks are referred to a doctor or sent to the hospital. “We also want to be able to confidently determine when a client is no longer at risk and may be medically cleared to go back into a shelter. We are trying to prevent epidemics within shelters, which would be very difficult to manage.”

Natalie Abad was volunteering at the COVID-19 FIU testing site when she heard about the homeless initiative from a classmate and immediately signed up.

“As a medical student, it’s been challenging to take a back seat during this pandemic and not be able to help. This was a very humbling way for me to provide support to one of the most vulnerable communities being affected,” she said.

Natalie and her teammate, Raquel Gil, were assigned a homeless man in isolation at a hotel in Overtown. During their calls, they discussed his feelings of isolation, symptoms, and any other concerns.

“He couldn’t stop expressing his gratitude,” she said. “He looked forward to our daily phone calls.”

Although some of the clients don’t speak English, communication is not a problem.

“Mr. Aristide speaks Creole, so we use a medical translation service to interpret for us during the calls,” said Korek.

The students often help with things that have nothing to do with the virus. They make sure their clients have clothing, toiletries, medication refills. Just as important, they provide a human connection.

Aristide beat the virus. He is now out of isolation and living in a shelter. But the phone calls haven’t stopped. They are not as often, but at his insistence, Korek and Gill continue to call. “This mean[s] a lot to me,” he said.